By John Ruggiero, PhD, MPA1,2, Antonio B. Meo, CHCP1, M. Theresa Bishay, PharmD1, Brigitte Azzi, PharmD1, Osarumen Urhoghide, PharmD1, and Gail Malnarick1

Before reading this article, take a look at part 1, which outlines the description and rationale for this study.

Daiichi Sankyo’s Medical Proficiency Acceleration Center (MPAC) developed a 20-question quantitative and qualitative survey with Likert-like scales to assess clinicians’ level of confidence on clinical topics prior to completing their CE. Complementary open-ended questions allowed them to retrospectively examine practice notes after the CE completions and document how their recent clinical actions were matched and resulting from those CE activities. Responses to all survey questions were encouraged but not required and due within 45 days upon receipt of the survey. The survey also captured the total number of CE activities completed, clinicians’ years in practice, their practice setting, areas of specialty and preferences for educational formats.

Between March 17, 2022, and May 11, 2022, Med Learning Group, an independent CE provider unaffiliated with Daiichi Sankyo, offered to disseminate the survey to (and collected the results from) a random sampling of their U.S. members, as well as those within the Public Health Foundation Network and a variety of oncology-based associations. Criterion for inclusion were those who participated in one or more in-person or online CE utilizing decision science techniques, but designed exclusively for knowledge outcomes, and completed within six months immediately prior to completing the survey. Only those who opted into the survey for the purposes of exploratory research were included. Clinicians who were no longer practicing prior to the completion of their CE were excluded. The survey results were blinded to Daiichi Sankyo and returned with unique identifiers. The results were not double blinded, as clinicians were aware that Daiichi Sankyo was conducting the study.

Of the 499 clinicians who returned responses, 47% were physicians (MD, DO), 19% registered nurses, a combined 14% physician associates and advanced practice nurses, 3.6% researchers and 1.8% pharmacists, with the remaining participants comprised of nurse specialists, nursing assistants, technicians and genetic specialists. The majority of participants (65.8%) were community practitioners, with 23.8% representing academic institutions and 10.4% representing a regional clinical network. Participation was diverse in that 26.8% practice in oncology, 12.2% in family medicine, 9.8% in internal medicine, 7.8% in neurology, 3.8% in psychiatry and 2.4% in surgery, with the remaining representing specialties across allergy and immunology, anesthesia, dermatology, emergency medicine, obstetrics and gynecology and pathology. These clinicians were not monetarily incentivized to respond.

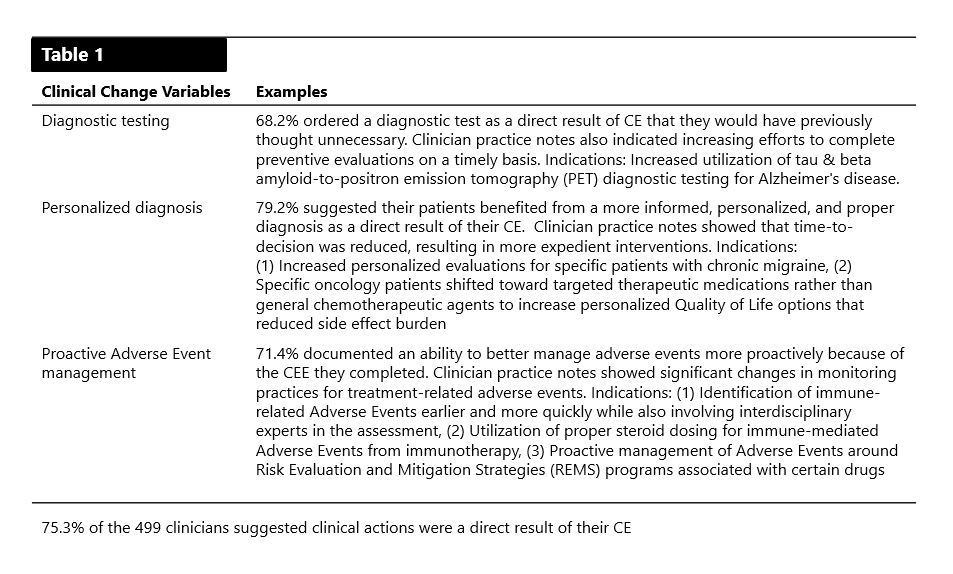

Two hundred sixty-four clinicians (53%) documented specific practice changes that they attributed to their CE. More directly though, 75.3% of the 499 clinicians suggested the CE helped them enhance personalized diagnoses, order diagnostic tests and alter care plan implementation habits, which we translated as practice change.

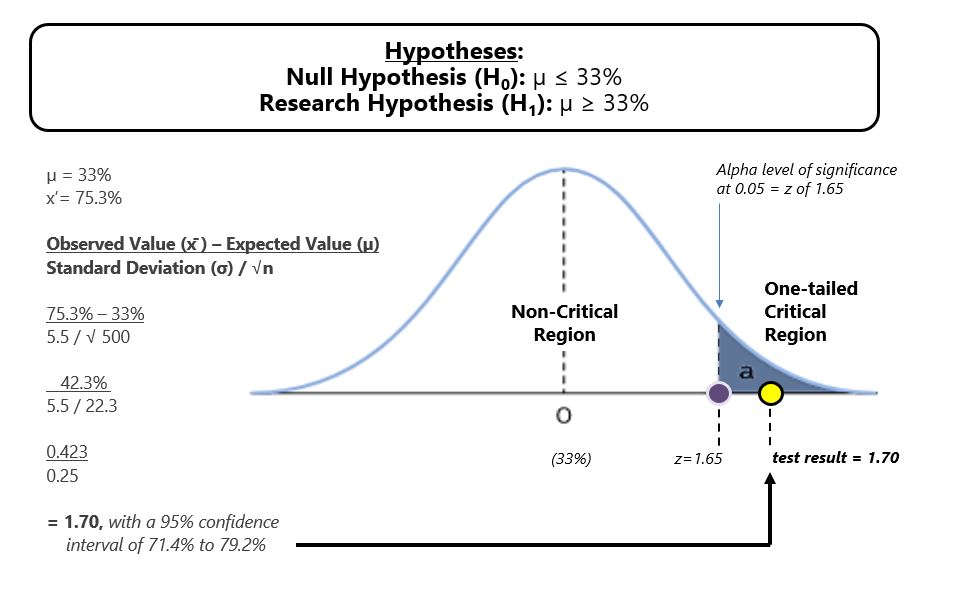

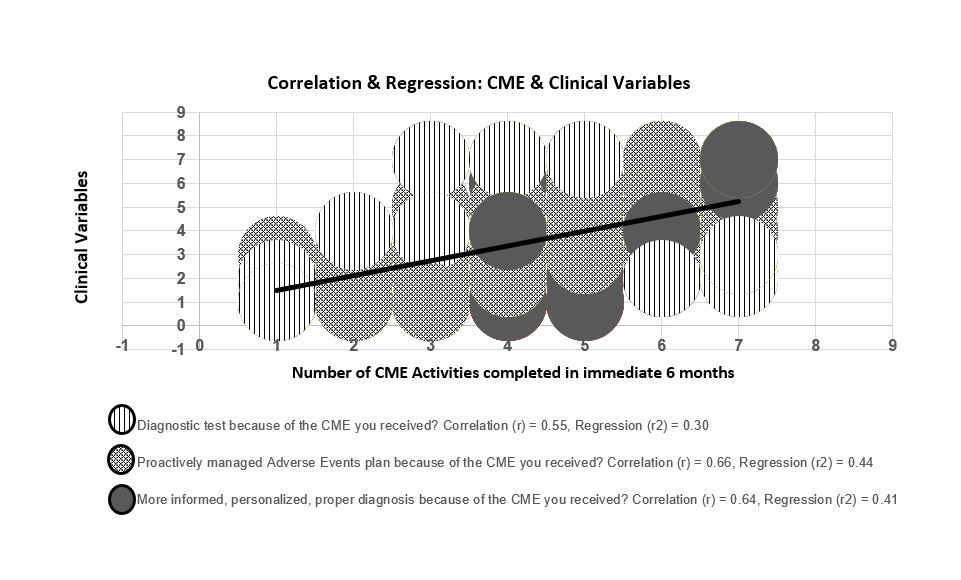

A directional hypothesis test with 0.5 alpha level of significance demonstrated with 95% confidence that previous research (33%) could therefore be updated. Additional Pearson correlation testing (r) indicated a positive relationship between knowledge-based CE and management of diagnostic tests, adverse events and personalized care plans (r=0.55, 0.64 and 0.66, respectively), with positive linear regression (r2=0.30, 0.41 and 0.44, respectively). There was no statistical difference when participant data was clustered by time and practice setting, indicating that practice change can occur across clinical specialties and practices, irrespective of a clinician’s time in practice if CE was effectively designed to primarily improve knowledge.

Our research hypotheses results were peer-reviewed and considered statistically accurate. The research also concluded with 95% confidence that the sample mean of 75.3% of clinicians demonstrating practice change could be representative of the full clinician population. In short, were similar research to be replicated, the confidence range expanded the mean to 71.4% to 79.2% of clinicians who potentially change as a result of some of their effective knowledge-based CE, provided the CE followed decision science techniques. In addition, a relationship between recurring knowledge-based CE activities and practice change variables was indeed observed.

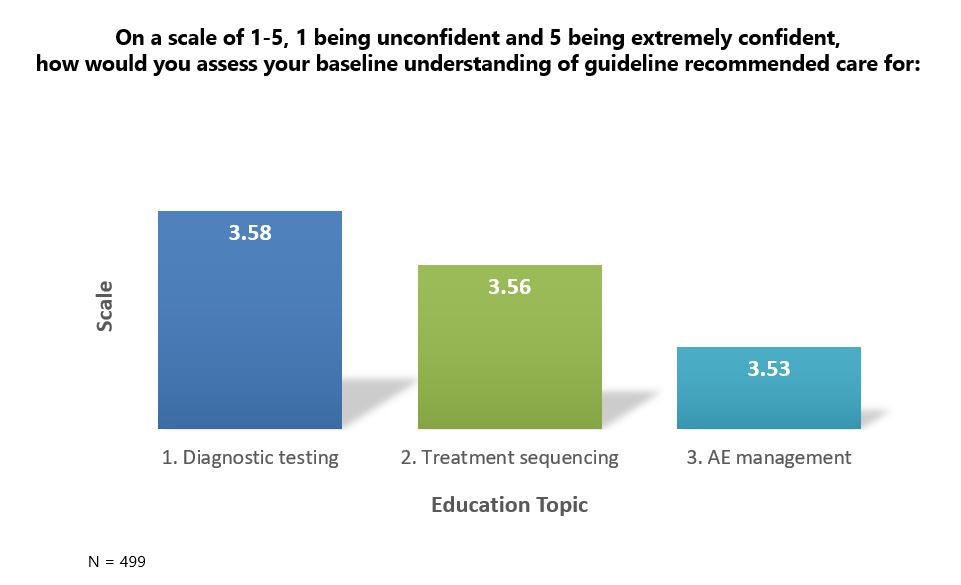

This is further amplified when analyzing the results against how clinicians rated their prior baseline level of understanding of guideline-recommended care for diagnostic testing, treatment sequencing and adverse event management. Using a five-point Likert-like scale, with 5 demonstrating full confidence, clinicians rated their understanding as 3.58, 3.56 and 3.53, respectively. This indicates that even clinicians who maintained a higher level of confidence in understanding still used the knowledge-based CE to initiate practice change, though the measure was self-rated and is therefore subject to the limitations of personal biases.

A core strength of the study was the use of a randomized sample of clinicians from various institutions and specialties, which provided a diversified sample of CE learners. Further, Daiichi Sankyo was not involved in the selection of learners, eliminating potential bias from participant objectivity to the questions being asked. Since some data were collected in a numeric form, statistical tests were applied allowing for a confident analysis derived from pertinent information. The qualitative data derived from responses to the open-ended questions allowed clinicians to provide details about how CE impacted their practice.

There are, however, limitations to this study. We recognize that change is influenced by multiple complex factors, as is the motivation for change. It is further recognized that change itself may not always directly translate as an improvement, and continued efforts should be made to analyze this. As with most educational studies where participants can be influenced by multiple factors outside of their education, this one was also not controlled to investigate outside factors that could also have influenced practice change. Further, because it was challenging to analyze multiple bodies of literature on an actual direct comparison of the impact on practice resulting from CE built exclusively to measure knowledge, statistical and probable extrapolations between medical information and CE were necessary. We encourage interested readers to continue this conversation by doing further research to examine whether or not different clinical disciplines, settings, educational formats, and any control over outside influences, if possible, would determine a more granular data analysis. Future researchers might consider analyzing all of these limitations with evidence-based methods, including but not limited to one- and two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to test for significant differences between variables being studied.

Nonetheless, this present work provides significant lessons for practice. The effectiveness of CE is its ability to disseminate and instill the latest advances in science and medicine to large clinician audiences, as well as its ability to engage learners in critical thinking, self-reflection and clinical performance. Rayburn et al. references professional and ethical behaviors that drive clinicians to intentionally seek out CE to build upon what they already know and to reinforce their knowledge, build confidence in practice and administer quality care.9 These data reinforce the importance of providing a robust curriculum of CE, which includes activities built exclusively to measure knowledge-based outcomes, engaging in different and multiple modalities of educational interventions and platforms, and providing clinicians access to education often and repeatedly to better instill the drive for lifelong learning and development.

It is our perspective that the educational community would benefit from three critical considerations. First, rather than reinventing the approach to CE and innovating for the sake of change, we should revisit the basics, embrace what works, and incorporate what clinicians are reporting as their needs and educational activity preferences. We should instead innovate through a reexamination of the way we measure outcomes and report their narrative, and never again assume a lower level of outcomes is lesser, especially if the data leads to meaningful change. Second, in par with the previous recommendation, existing outcomes models can be complemented with other existing and simple models that are transferable across disease states. Finally, we should study and then accurately incorporate decision science into the development of CE activities. Educational content, materials and measurement questions can all be designed to assess clinical reasoning, which when reported could be far more effective than simply reporting the average percentage of improvement on activity objectives. Daiichi Sankyo’s MPAC will be issuing a white paper in the first half of 2023 that further details the information and data analysis of this study and provides a philosophy and guided examples on each of the three above considerations.

The perspectives expressed within the content are solely the authors and do not intend to suggest a reflection on the opinions and beliefs of those with whom we’d like to acknowledge for their review and contributive feedback: Mr. Matthew Frese, MBA, general manager of Med Learning Group; Ms. Aimee Meissner, accreditation and outcomes coordinator of Med Learning Group; Ms. Lauren Welch, MA, senior vice president for outcomes and accreditation of Med Learning Group; Dr. Brian McGowan, PhD, FACEhp, chief learning officer and co-founder of ArcheMedX, Inc.; Ms. Pamela Mason, BS, CHCP, FACEhp, ATSF, senior director for medical education grants office of AstraZeneca PLP, and clinical adjunct associate professor, Keck Graduate Institute, School of Pharmacy & Health Sciences; Mr. Ivan Desviat, director global medical education excellence for Abbvie; Ms. L.B. Wong, RN, MSN, MBA, senior director of independent medical education for Eli Lilly and Company; Ms. Patricia Jassak, MS, RN, FACEhp, CHCP, director of independent medical education and medical external affairs for Astellas; Ms. Greselda Butler, CHCP, FACEhp, director of independent medical education strategy and external affairs for Otsuka; Ms. Suzette Miller, MBA, CHCP, FACEhp, director of medical education grants and sponsorships for Genmab.

References

- Moore DE, Jr. A framework for outcomes evaluation in the continuing professional development of physicians. In: Davis D, Barnes BE, Fox R, eds. The continuing professional development of physicians:From research to practice. American Medical Association Press; 2003:249-274.

- Source: Harvard T.H. Chan. Center for Health Decision Science. https://chds.hsph.harvard.edu/approaches/what-is-decision-science/. Accessed November 10, 2022.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). (2022). “CME Content: Definition and Examples.” https://www.accme.org/accreditation-rules/policies/cme-content-definition-and-examples. Accessed May 24, 2022.

- Deilkås, E.T., Rosta, J., Baathe, F. et al. Physician participation in quality improvement work- interest and opportunity: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Prim. Care 23, 267 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01878-6

- Source: McKinsey Leadership Summit in Medical Education, 2021.

- Richards RK, Cohen RM. Why physicians attend traditional CME programs. J Med Educ. 1980;55(6):479-485. http://www. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7381898/. Accessed May 24, 2022.

- Olson, C.A., Tooman, T.R. Didactic CME and practice change: don’t throw that baby out quite yet. Adv in Health Sci Educ 17, 441–451 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-011-9330-3

- Marshall JG, Sollenberger J, Easterby-Gannett S, Morgan LK, Klem ML, Cavanaugh SK, Oliver KB, Thompson CA, Romanosky N, Hunter S. The value of library and information services in patient care: results of a multisite study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2013 Jan;101(1):38–46.

- Rayburn WF, A D, Turco M. Continuing Professional Development in Medicine and Health Care : Better Education, Better Patient Outcomes. Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

Authors

1Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Medical Proficiency Acceleration Center, Medical Affairs

2Drexel University College of Nursing and Health Professions, Adjunct Faculty Member for Biostatistics, Epidemiology & Research Methods

|

John Ruggiero, PhD, MPA1,2

|

Antonio B. Meo, CHCP1

|

M. Theresa Bishay, PharmD1

|

|

Brigitte Azzi, PharmD1

|

Osarumen Urhoghide, PharmD1

|

Gail Malnarick1

|