By John Ruggiero, PhD, MPA1,2, Antonio B. Meo, CHCP1, M. Theresa Bishay, PharmD1, Brigitte Azzi, PharmD1, Osarumen Urhoghide, PharmD1, and Gail Malnarick1

This study by Daiichi Sankyo uncovered significant clinical developments that resulted from accredited continuing medical education (CME) exclusively built to measure Level 3 knowledge outcomes1, sometimes overlooked in conversations about the merit of CME. Debates in recent clinical and educational forums have suggested an insufficient body of evidence may exist that correlates practice change with knowledge improvement CME or broader continuing education and continuing professional development (which henceforward for the purposes of this discussion we will term together as CE). It is our perspective that such thoughts are not completely inaccurate but perhaps misguided and unintentionally underestimate the value of knowledge acquisition, provided the content and pre- and post-test questions are structured in clinical reasoning and decision science. Defined as the process of making optimal choices based on available information, decision science seeks to make plain the scientific issues and value judgments of underlying decisions so that tradeoffs can be made for any particular action or inaction.2 We therefore determined that additional evidence would further establish this correlation between knowledge and practice while enhancing the current inventory of literature related to this topic.

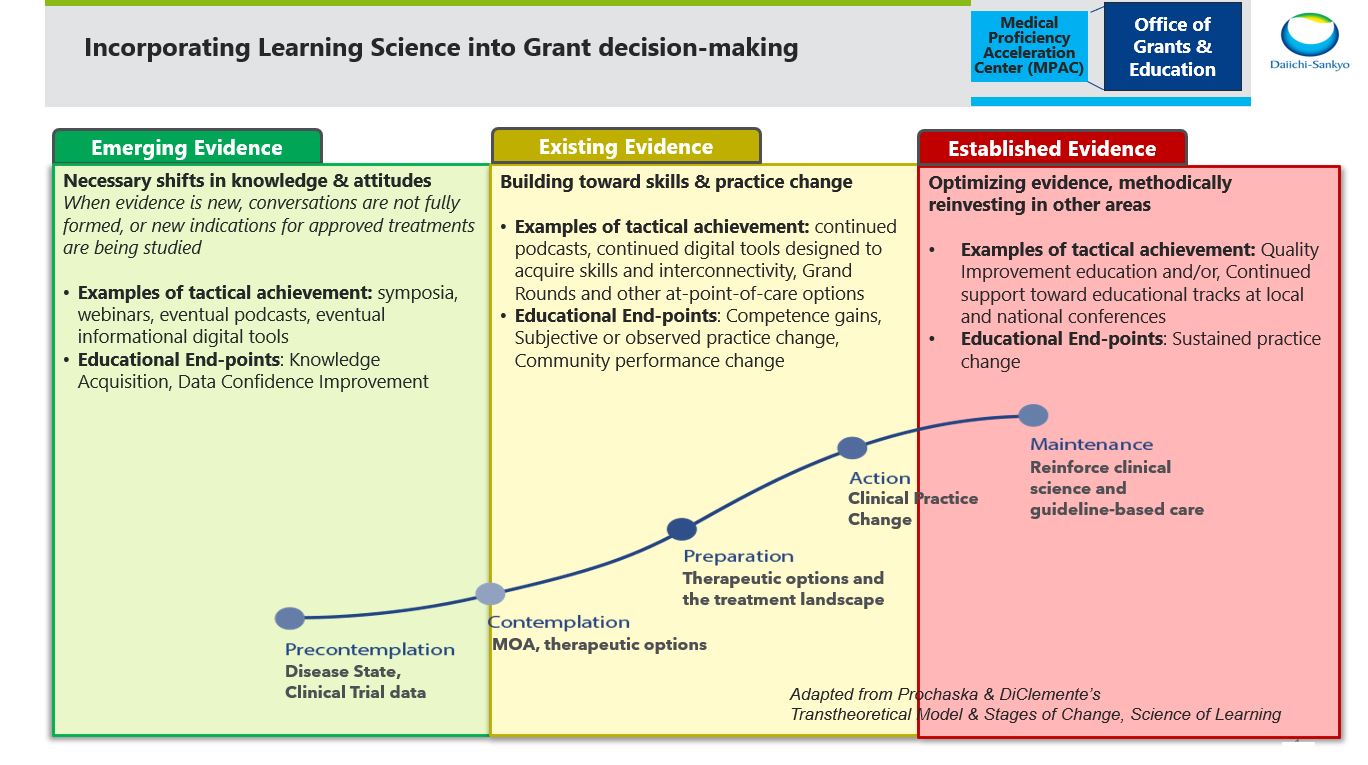

The content of CE is comprised of a body of knowledge and skills generally recognized and accepted by the profession as within the basic medical sciences, the discipline of clinical medicine and the provision of healthcare to the public.3 For this reason Daiichi Sankyo incorporates learning science into educational support decisions, believing all types of outcomes levels have equal weight in the gap continuum.

In fact, Daiichi Sankyo does indeed support education and other initiatives that are embedded at the point of care and result in individual and community practice change measures. There are, however, evolving requirements facing specialists in the pre- and perioperative settings that are reinforcing the importance of deep knowledge transfer, either as an initial step or sometimes as the sole purpose of an educational initiative. Such requirements include consistently progressing clinical guidelines which are heavily reliant on knowledge transfer, and models developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to inform the Alternative Performance Pathways (APPs). Primary Care First, Realizing Equity, Access and Community Health (REACH), the Medicare Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART), and the Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM) are just some of the models that follow the APP guidance. Most recently, CMS has been preparing clinicians to replace the Oncology Care Model with the EOM, partly because of the importance it places on knowledge-building measures around patient centeredness. Like many others, we propose that CE exists to help optimize medical evidence and to accelerate science into the clinical decision-making process. Often, depending on the timing of the evidence cycle, the best solution may in fact be CE that is exclusively based in declarative and procedural knowledge-building.

Many recent disruptions have challenged our community to innovate simultaneously to clinicians and patients being faced with a rapid pace of scientific evidence. Through a healthy reexamination of approaches, however, we must be cautious not to mistake knowledge outcomes as invaluable to stakeholders. We also must not revolutionize simply for the sake of change. In fact, Ellen Tveter Deilkås et. al. conducted a 2022 study which discovered that 85.7% of 2,085 physicians wanted to participate in quality improvement initiatives, yet only 16.7% reported time designated for quality improvement in their own work hours.4 Further, in a cross-industry medical affairs leadership summit, McKinsey reported that 75% of 2,050 surveyed physicians have been using medical information and CE to improve their knowledge and skills, yet 56% suggested they are experiencing unsustainable workloads. Thus, 50% still prefer quick, individualized self-service means of education despite our best efforts to get them engaged in innovative educational approaches.5 Because objective practice change education often requires planning, doing, studying and acting on results, it is perhaps most effective when preference to participate has been carefully secured. It is our perspective that this is indeed possible when the consequences of not being involved have been made most clearly meaningful to clinicians.

Clinician participation tends to be motivated by the need to satisfy specific professional requirements as well as personal reasons, ranging from topic interest to a change of pace from routine practice.6 However, for some clinicians, CE community members and even industry leaders, the question remains if and how clinician involvement in CE effects practice change. We believed that examining prior evidence related to the direct effect improved knowledge alone has on practice change was an important step to appropriately analyze this study. A Google Scholar search on Nov. 18, 2022, on "knowledge-based CME/CE impacts clinician practice change" returned 3,010 references. While we honor these works and respect all of the contributions to the conversation, the majority were published an average of 10 or more years ago. Of those publications that specifically aimed to correlate knowledge to practice change, some significant gains were observed. However, most of the results were self-reported percentages of intention to change practice without many, if any, statistical specifics in actual observed patient cases. CE is not a homogenous set of interventions, and despite the 3,010 references, there were still challenges gaining access to evidence-based publications on the direct correlations of this topic. We therefore appreciate why some continue to debate if knowledge-based education actually results in changes that are incorporated into clinical practice.

We more deeply examined two of those discovered resources to use as comparisons to our own. The first in which Curtis A. Olson and Tricia A. Tooman in 2012 argued that the impact of didactic educational methods has been systematically under-recognized. They concluded that more research was needed on the phenomenology and natural history of change, and that “pegging the value of an educational method directly to practice change and patient outcomes overlooks a broad range of potentially valuable, even critical, contributions the method can make to professional development and practice change.”7 Their work is less a study and more an equally important reflection focused on a specific format, didactic CME rather than education built for the primary purpose of exclusively measuring knowledge. Second, we focused on the 2012 work of JG Marshall et al. While it was not research specifically on CE, we made an extrapolation due to the aforementioned challenges. Marshall’s research focused on the impressions made from medical information sources. It was discovered that 59% of 16,000 clinicians searching for information or education satisfactorily discovered what they sought, and 95% found the information provided in the resources to be relevant, accurate and current. Yet only up to 33% said the information altered their therapeutic choices and procedural approach to patient care.8 It may be reasonable to suggest that the data from this study might have been an underrepresentation of the impact on practice change resulting from CE.

Therefore, we hypothesized that CE based in knowledge acquisition (the independent variable) can directly impact practice change (the dependent variable) if designed with probing motivational decision science material. More specifically, we believed the mean of clinicians that change practice as a result of knowledge-based CE is actually greater than the previously reported 33%. We also hypothesized that clinicians who completed recurring CE activities of a similar disease gap or therapeutic topic (the independent variable) would demonstrate a stronger rate of practice change (the dependent variable) over time.

Stay tuned for part 2 of this article to learn more about the survey the Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., team developed and distributed through MLG.

The perspectives expressed within the content are solely the authors and do not intend to suggest a reflection on the opinions and beliefs of those with whom we’d like to acknowledge for their review and contributive feedback: Mr. Matthew Frese, MBA, general manager of Med Learning Group; Ms. Aimee Meissner, accreditation and outcomes coordinator of Med Learning Group; Ms. Lauren Welch, MA, senior vice president for outcomes and accreditation of Med Learning Group; Dr. Brian McGowan, PhD, FACEhp, chief learning officer and co-founder of ArcheMedX, Inc.; Ms. Pamela Mason, BS, CHCP, FACEhp, ATSF, senior director for medical education grants office of AstraZeneca PLP, and clinical adjunct associate professor, Keck Graduate Institute, School of Pharmacy & Health Sciences; Mr. Ivan Desviat, director global medical education excellence for Abbvie; Ms. L.B. Wong, RN, MSN, MBA, senior director of independent medical education for Eli Lilly and Company; Ms. Patricia Jassak, MS, RN, FACEhp, CHCP, director of independent medical education and medical external affairs for Astellas; Ms. Greselda Butler, CHCP, FACEhp, director of independent medical education strategy and external affairs for Otsuka; Ms. Suzette Miller, MBA, CHCP, FACEhp, director of medical education grants and sponsorships for Genmab.

References

- Moore DE, Jr. A framework for outcomes evaluation in the continuing professional development of physicians. In: Davis D, Barnes BE, Fox R, eds. The continuing professional development of physicians:From research to practice. American Medical Association Press; 2003:249-274.

- Source: Harvard T.H. Chan. Center for Health Decision Science. https://chds.hsph.harvard.edu/approaches/what-is-decision-science/. Accessed November 10, 2022.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). (2022). “CME Content: Definition and Examples.” https://www.accme.org/accreditation-rules/policies/cme-content-definition-and-examples. Accessed May 24, 2022.

- Deilkås, E.T., Rosta, J., Baathe, F. et al. Physician participation in quality improvement work- interest and opportunity: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Prim. Care 23, 267 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01878-6

- Source: McKinsey Leadership Summit in Medical Education, 2021.

- Richards RK, Cohen RM. Why physicians attend traditional CME programs. J Med Educ. 1980;55(6):479-485. http://www. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7381898/. Accessed May 24, 2022.

- Olson, C.A., Tooman, T.R. Didactic CME and practice change: don’t throw that baby out quite yet. Adv in Health Sci Educ 17, 441–451 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-011-9330-3

- Marshall JG, Sollenberger J, Easterby-Gannett S, Morgan LK, Klem ML, Cavanaugh SK, Oliver KB, Thompson CA, Romanosky N, Hunter S. The value of library and information services in patient care: results of a multisite study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2013 Jan;101(1):38–46.

- Rayburn WF, A D, Turco M. Continuing Professional Development in Medicine and Health Care : Better Education, Better Patient Outcomes. Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

Authors

1Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Medical Proficiency Acceleration Center, Medical Affairs

2Drexel University College of Nursing and Health Professions, Adjunct Faculty Member for Biostatistics, Epidemiology & Research Methods

|

John Ruggiero, PhD, MPA1,2

|

Antonio B. Meo, CHCP1

|

M. Theresa Bishay, PharmD1

|

|

Brigitte Azzi, PharmD1

|

Osarumen Urhoghide, PharmD1

|

Gail Malnarick1

|