“To attend those who suffer, a physician must possess not only the scientific knowledge and technical abilities, but also an understanding of human nature. The patient is not just a group of symptoms, damaged organs and altered emotions. The patient is a human being, at the same time worried and hopeful, who is searching for relief, help and trust.”¹

Origin Story and Culture

The historical relationship between doctors and patients has traditionally been paternalistic, with the patient's role in the medical decision-making process being largely passive. As early as the 1960s, this dynamic was reflected in the early stages of continuing medical education (CME), where patients' involvement was primarily as subjects in role-playing exercises designed to enhance clinicians' physical examination skills.² However, the evolution of the clinician-patient relationship — spurred by advances in medical technology, a growing emphasis on patients' rights and changes in healthcare policies — has dramatically transformed the role of patients in CME.¹ Since the 1990s, the culture within medicine has shifted toward a more collaborative and empowering model, with patients assuming active roles as educators and consultants.³

Why Patient Partnership Matters

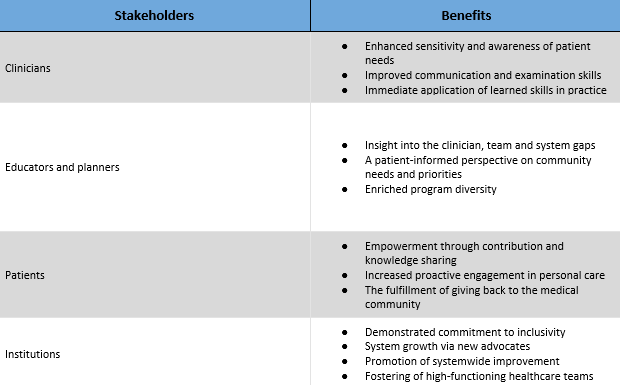

The patient as the teacher not only provides a nuanced perspective but also engages clinicians in a meaningful way.² Strategically including patients in CME can provide a real-life perspective on disease, facilitate the shared decision-making process and, most importantly, improve patient outcomes.⁴,⁵ This holistic approach enhances the relevant impact for continuing professional development (CPD), fosters sensitivity among clinicians to patient needs, bridges gaps in medical education through real-world insights and symbolizes a systemic commitment to inclusivity and improved patient-centered care.⁵,⁶ The table below demonstrates the value of patient-partner involvement to all stakeholders.

Table 1: The Multi-Dimensional Value of Patient Involvement in CME based on “Learning Together: Engaging Patients as Partners in CPD” by Graham T. McMahon, MD, MMSc

Involving the Patient-Partner

The level of a patient-partner involvement can occupy a wide spectrum. Participation can range from the less intensively involved, such as contributing to paper-based or electronic case scenarios, to more intensively involved at the institutional level. Whatever the involvement level, it is crucial to explore practical strategies for maximizing this engagement. By implementing effective tactics, healthcare professionals can harness the valuable insights patients bring to the table and enrich the learning experience for clinicians.²,⁷

Recently, an article titled, "Twelve Tips for Patient Involvement in Health Professions Education" provided guidance on how to effectively involve patients in the health professions educational process. The recommendations were:

1.. Cultivate an environment that values openness and provides unwavering support for patients.

2. Integrate patients into every aspect of education in a meaningful manner.

3. Strive for a diverse representation.

4. Acknowledge and value the educational contributions of patients.

5. Explore unconventional approaches beyond the typical patient lecture.

Potential Pitfalls

The tips mentioned earlier should not be seen as a universal solution but rather as a starting point. Achieving meaningful patient involvement in CME requires careful customization and thoughtful planning. In navigating this process, healthcare education professionals may encounter the following obstacles:

- Patients’ Reluctance: Patients' reluctance to share information can be a common challenge in healthcare education. The article "Patient-Partners as Educators: Vulnerability Related to Sharing of Lived Experience" discusses how patient-partners can evaluate their readiness using the wound versus scar analogy. Some stories are wounds requiring further healing before sharing, while others are scars fully processed and ready for public sharing. The authors also introduced the Sender-Receiver Model of Communication for Patient-Partners. This model highlights the importance of recognizing the vulnerability of patient-partners’ stories and how the clinician audience can differentiate between thought-provoking questions and potential "personal attacks". It is recommended to incorporate pre-session and post-session debriefs to allow both patient-partners and audiences to process and navigate the intense emotions that sharing stories may evoke.⁷

- Clinician Resistance: Resistance from some clinicians could be the result of common beliefs that patients do not possess scientific knowledge, objectivity and cannot effectively contribute to medical education.⁸ Reframing the process and highlighting the benefits of collaborative learning is important. The most valuable contribution to CME is the patient’s learned experience in living with a disease and the associated daily toll.³ Where the clinician can bring scientific knowledge, the patient can bring experiential knowledge.

- Tokenism and Ineffective Engagement: Failure to effectively empower patients for active participation can lead to tokenism and ineffective engagement. It is imperative to provide resources to help bolster patient-partners’ confidence and lower any associated anxiety. Recommendations include meeting with the patient-partner to discuss details about the educational activity, regularly communicating with them and honoring their contribution.⁹,¹⁰

Recap

The journey toward actively integrating patient-partners into CME reflects a significant cultural shift within the medical field. From their initial passive involvement to the current emphasis on strategic and meaningful engagement, the patient-partner narrative is evolving. This evolution underscores the critical importance of recognizing individuals receiving care not merely as patients but as knowledgeable partners contributing invaluable perspectives to medical education.

The transformation from patient to partner signifies more than a change in terminology. It represents a profound shift in the healthcare culture toward inclusivity, shared decision-making and mutual respect. By valuing the lived experiences and insights of patient-partners, healthcare professionals can enhance the quality of education and, consequently, patient care outcomes. The challenges outlined, including patients' vulnerability and clinician resistance, are reminders of the complexity of this integration but also emphasize the potential for a profound impact on educational outcomes and healthcare delivery.

Additional Resources

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education Patient Engagement Resources

- Patient Voices Network. A Guide to Authentic Patient Engagement. (n.d.). https://patientvoicesbc.ca/resources/a-guide-to-patient-engagement/

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Guide to Patient and Family Engagement in Hospital Quality and Safety

- Rayburn, W. F., & Davis, D. A. (2018b). Continuing professional development in medicine and Health Care: Better Education, Better Patient Outcomes. Wolters Kluwer.

1. Hellín T. The physician-patient relationship: Recent developments and changes. Haemophilia. 2002 May;8(3):450-4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2002.00636.x. PMID: 12010450.

2. Towle A, Bainbridge L, Godolphin W, Katz A, Kline C, Lown B, Madularu I, Solomon P, Thistlethwaite J. Active patient involvement in the education of health professionals. Med Educ. 2010 Jan;44(1):64-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03530.x. PMID: 20078757.

3. McKay J, Needham E, Walsh W. Including Patient Voices in Continuing Medical Education: One Provider's Experience. J CME. 2023 Nov 5;12(1):2275504. doi: 10.1080/28338073.2023.2275504. PMID: 37942272; PMCID: PMC10629417.

4. Pazirandeh M. Does patient partnership in continuing medical education (CME) improve the outcome in osteoporosis management? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002 Summer;22(3):142-51. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340220303. PMID: 12227236.

5. Wykurz G, Kelly D. Developing the role of patients as teachers: literature review. BMJ. 2002 Oct 12;325(7368):818-21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7368.818. PMID: 12376445; PMCID: PMC128951.

6. McMahon GT. Learning Together: Engaging Patients as Partners in CPD. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2021 Oct 1;41(4):268-272. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000388. PMID: 34609358.

7. Metersky K, Rahman R, Boyle J. Patient-Partners as Educators: Vulnerability Related to Sharing of Lived Experience. Journal of Patient Experience. 2023;10. doi:10.1177/23743735231183677.

8. Chu, Larry & Utengen, Audun & Kadry, Bassam & Kucharski, Sarah & Campos, Hugo & Crockett, Jamia & Dawson, Nick & Clauson, Kevin. (2016). “Nothing about us without us”—patient partnership in medical conferences. BMJ. 354. i3883. 10.1136/bmj.i3883.

9. Patient Voices Network. A Guide to Patient Engagement. BC Patient Safety & Quality Council. Available at: https://bcpsqc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/PVN_Getting-Started-with-Patient-Engagement_WEB.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2024.

10. ACCME. 12 Tips for Engaging Patients [PDF]. Retrieved from ACCME website: https://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/2018-03/760_20170814_12_Tips_for_Engaging_Patients.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2024.

Milini Mingo, MPA, CHCP, has been in the continuing medical education field for several years. Milini’s work focuses on adult learning, program development, translational initiatives/content and accreditation.

Milini Mingo, MPA, CHCP, has been in the continuing medical education field for several years. Milini’s work focuses on adult learning, program development, translational initiatives/content and accreditation.