Learning objectives often look simple — consisting of just a single sentence — but they can be deceptively challenging to write. Objectives define what learners should know or be able to do after completing a CE activity. In this way, they help transform educational gaps — what clinicians know and do in practice versus what they should know or do based on the latest evidence — into concrete steps that drive improvement. To be effective, learning objectives must align with measurable outcomes that demonstrate a change in clinician competence, performance or patient outcomes. Yet expressing this concept in a clear, concise statement is not easy. So, how can we write objectives in a way that supports high-quality education?

Addressing this question begins with understanding why learning objectives matter in CE. Serving several key purposes, they:

- Orient learners, providing a clear sense of what participants can expect to learn and how it will benefit their practice.

- Guide the educational content, ensuring that the material presented is relevant to learners’ needs.

- Establish the basis for evaluation, determining how outcomes will be assessed.

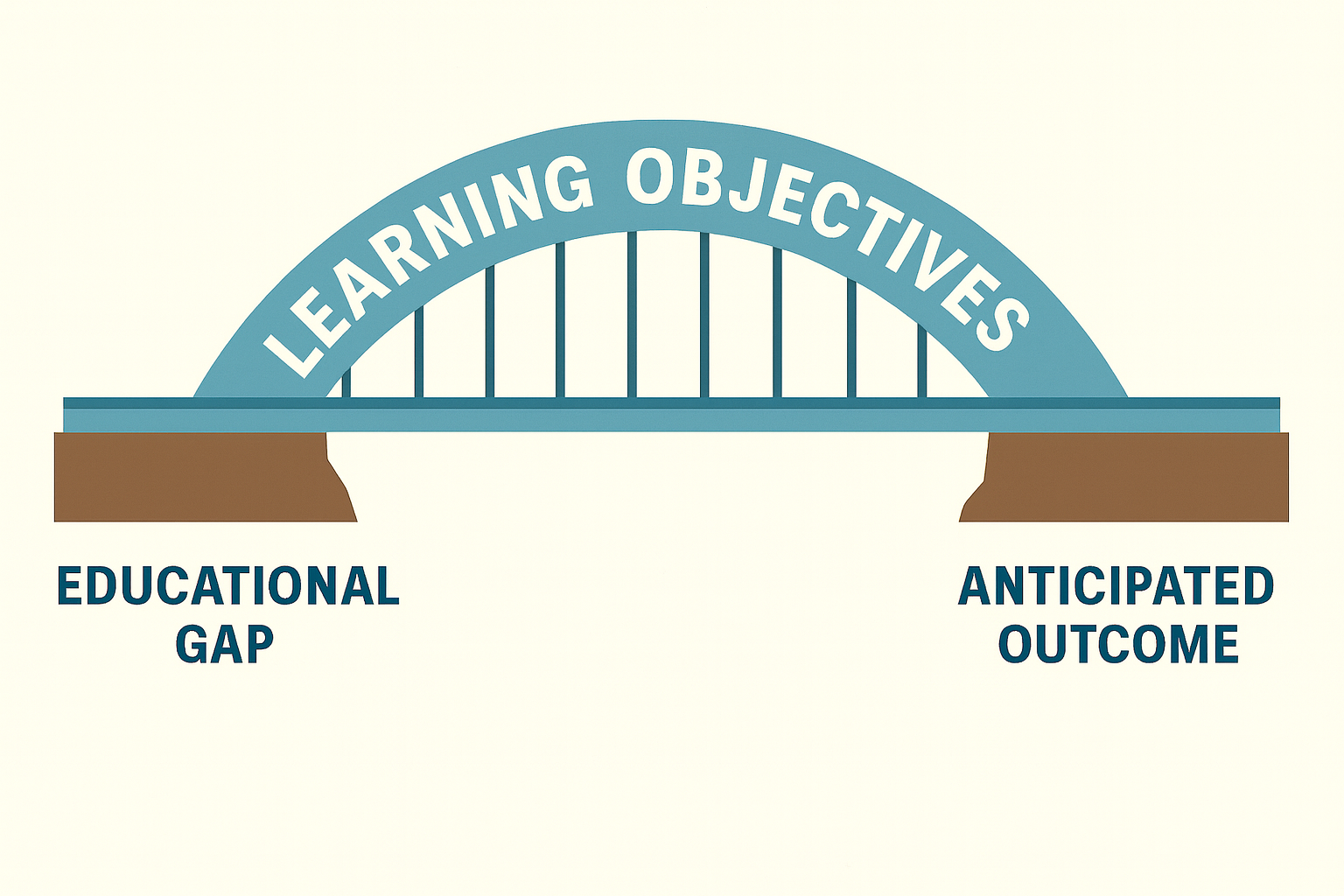

The connection between learning objectives and outcomes is essential to educational design.

Learning objectives serve as the bridge between the identified educational gap and the anticipated outcome. They connect what learners need — whether it’s new knowledge, updated clinical skills or improved communication strategies — to what the activity aims to achieve. In other words, learning objectives are actionable. They move the learners from where they are to where they should be.

Most CE activities align with Moore’s level of outcomes — most commonly level 3 (knowledge), level 4 (competence) and level 5 (performance). In addition to Moore’s framework, other useful models can guide the development of learning objectives. Bloom’s taxonomy classifies objectives by cognitive complexity, from basic recall to higher-order skills such as analysis, evaluation and creation. The SMART model specifies that objectives should be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time-bound. The ABCD framework defines four components: audience, behavior, condition and degree. Similarly, the Kearn and Thomas approach focuses on who will do how much, how well, of what, by when. While these models all emphasize the importance of writing measurable, achievable learning objectives, Moore’s is commonly used in CE and will serve as the primary framework in this article.

Components of Effective Learning Objectives

Effective learning objectives include the following components to reinforce how learners will improve their knowledge, skills and current practices:

Effective learning objectives include the following components to reinforce how learners will improve their knowledge, skills and current practices:

- Learning objectives begin with an actionable verb. This verb is arguably the most important part of the learning objective. It should describe an observable, measurable action that demonstrates what learners will do as a result of the activity. Most guidelines for writing learning objectives advise against using vague verbs such as understand, learn or comprehend. That is because these verbs are difficult to measure with standard tools such as pre- and post-tests. Instead, verbs that align with an outcomes framework such as Moore's should be used to signal whether the activity is targeting knowledge, competence or performance.

- Level 3 (knowledge): At this level, learners acquire information or concepts but are not yet expected to demonstrate application. Common verbs include define, list, identify and describe.

- Example: Describe the mechanism of action of SGLT2 inhibitors.

- Example: Identify the risk factors associated with the progression of chronic kidney disease.

- Level 4 (competence): Learners demonstrate their ability to apply knowledge in an educational setting, such as case-based discussions, simulations or assessments. Useful verbs include analyze, assess, develop and evaluate.

- Example: Assess the latest clinical evidence on therapies for patients with severe asthma.

- Example: Develop multidisciplinary care strategies to improve the management of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

- Level 5 (performance): Learners are expected to carry new skills or strategies into their actual practice. Verbs such as apply, implement, integrate and incorporate reflect changes in real-world behavior.

- Example: Implement evidence-based treatment strategies for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

- Example: Integrate biomarker testing into clinical decision-making for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer.

- Learning objectives express a single action. Each learning objective should include only one verb. Combining multiple actions in a single statement creates confusion about what is being measured. Consider the following example:

Review the referral criteria for timely referral, and outline a multidisciplinary approach to provide continuity of care for patients with suspected skin cancer.

This learning objective has two verbs — review and outline — that represent distinct tasks: (1) deciding when to refer patients and (2) coordinating multidisciplinary care. To fix this issue, the learning objective could be split into two so each objective remains focused and measurable:

- Review the criteria for the timely referral of patients with suspected skin cancer for further evaluation.

- Outline a multidisciplinary approach to provide continuity of care for patients with skin cancer.

- Learning objectives are focused and achievable. A learning objective should emphasize one main idea. Even learning objectives that contain only one verb are not actionable or measurable if they attempt to address several goals. For example, the following learning objective lacks a specific focus:

Review the disease burden, pathophysiology, diagnosis and unmet patient needs associated with rheumatoid arthritis.

This learning objective is “overstuffed” — burden, pathophysiology, diagnosis and unmet needs are separate topics. Depending on the activity’s length and the target audience, covering all may be unnecessary. While CE activities often aim to address many areas — especially when supported by multiple stakeholders — a focused objective offers greater value. Aligning one objective with a specific educational gap allows measurable insight into learners’ growth in knowledge, competence and practice.

- Learning objectives align with the audience’s needs. Learning objectives should take into account who the learners are and what they need to achieve in practice. A primary care physician may need to recognize warning signs and refer patients, while a specialist may need to apply diagnostic criteria or evaluate advanced therapies.

- Example for primary care physicians: Recognize clinical indicators of suspected psoriatic arthritis that warrant referral to a specialist.

- Example for specialists: Review the evidence-based diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis.

Learning objectives that are tailored to the audience ensure the activity remains relevant and impactful.

Examples for Avoiding Common Pitfalls in Learning Objectives

The following examples highlight common pitfalls in writing learning objectives and how to avoid them.

|

Example 1:

Have improved confidence in managing patients with ulcerative colitis.

|

Pitfall:

This objective lacks an actionable verb. While clinicians can rate their confidence, that doesn’t show knowledge or skill gain. Self-assessment can be unreliable — clinicians may feel confident yet perform poorly or feel uncertain despite competence. Using measurable verbs allows more accurate evaluation.

|

Stronger objective:

- Implement guideline-recommended strategies for managing patients with ulcerative colitis.

|

|

Example 2:

Summarize the diagnostic criteria for asthma and compare treatment strategies for severe cases.

|

Pitfall:

This objective includes two verbs, summarize and compare. If both topics are essential, they should be separate objectives.

|

Stronger objectives:

- Summarize the diagnostic criteria for asthma.

- Compare treatment strategies for patients with severe asthma based on the current clinical evidence.

|

|

Example 3:

Recognize the disease burden, clinical presentation and treatment options for patients with atrial fibrillation.

|

Pitfall:

This objective is “stuffed” with several distinct topics. Each should be addressed separately, if all fall within the activity’s scope.

|

Stronger objectives:

- Recognize the disease burden associated with atrial fibrillation.

- Identify the clinical presentation of atrial fibrillation.

- Assess guideline-based treatment strategies for patients with atrial fibrillation.

|

|

Example 4, intended to reflect Moore’s level 5: Assess guideline-based treatment strategies for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis.

|

Pitfall:

The verb assess aligns with Moore’s level 4 (competence), not level 5 (performance). It asks learners to analyze, not apply, information.

|

Stronger objective:

- Implement guideline-based treatment strategies for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in clinical practice.

|

Learning Objectives: A Foundational Tool

Learning objectives are written with the intent to improve the knowledge, skills and performance of healthcare professionals — and in this sense, they are an integral part of the larger goal of CE to improve patient outcomes. A well-crafted learning objective provides direction to a CE activity, showing how education can be translated into meaningful changes in real-world practice and ultimately driving advancements in patient care. Importantly, even as outcomes frameworks in CE for healthcare professionals continue to evolve, the concepts and tools presented here will remain constant as a foundation for bridging educational gaps to desired outcomes.

Further Resources for Writing Learning Objectives

- The Outcomes Standardization Project’s glossary provides descriptions of each of Moore’s levels.

- George Mason University offers an explanation of Bloom’s taxonomy, including appropriate verb choices.

- Harvard Medical School provides a primer on learning objectives that includes descriptions of the SMART model, Bloom’s taxonomy, and the ABCD framework.

Acknowledgement

I’d like to acknowledge Alexandra Howson, PhD, CHCP, FACEhp, E-RYT, for her contributions to this article, especially for sharing her insights on how to write learning objectives well and providing thoughtful feedback.