It has been said that the world’s body of scientific knowledge approximately doubles every 73 days.1 As continual re-skilling has become a permanent feature of work, the focus of CME has transitioned to competency-based continuing professional development, with an emphasis on developing what the learner is able to do versus what the learner knows.

What a learner can do comes from training in both skills and competencies. In business and in the training world, “skills” and “competencies” are similar terms with an intrinsic difference. Skills are the specific learned activities that are required to perform a job successfully, like coding, foreign language or handling accounts. Competencies are the experience and behaviors, such as strategic planning, problem solving or negotiation, which lead to success at a job. Put another way, “Competencies are the language of behavior; skills are the language of work.”2 Achieving maximum success at a job requires both, with required skills and competencies evolving throughout one’s career.

Because competencies are often developed by practicing particular skills, effective skills training, in which learners gain functional mastery through active learning and coursework that is transferable to the real world, can ultimately produce a more proficient workforce and better communicators or problem-solvers.

Skills Training for Healthcare Providers

Skills can be classified as “hard” or “soft.” In the healthcare field, hard clinical skills include the ability to perform a procedure or choose an appropriate medication for a particular patient, while soft skills include effective provider-patient interactions and intraprofessional communication necessary to provide patient care.

Indeed, the career search website has outlined the hard and soft skills that physicians need. They include3:

- Technical skills: Assessing symptoms, administering treatments, interpreting lab results and prescribing medication correctly

- Communication skills: Clear language, effectively communicating policies and procedures to other healthcare professionals, active listening, body language and providing feedback

- Problem-solving and critical thinking: Using logic and reasoning to identify and find solutions or approaches to problems

- Judgment and decision-making: Making decisions after examining both benefits and consequences of potential actions

- Interpersonal skills: Empathy, patience, compassion, professionalism, respect, cultural awareness and attitude

- Attention to detail: Observation, organization, time management, focus and attentivenes

Important differences in hard and soft skills include how they are obtained and how they are applied in the workplace. Medical schools and professional licensing boards are highly practiced and skilled at training and assessing healthcare providers in their essential clinical skills.

Continuing medical education is another highly effective modality for both hard and soft skills acquisition and enhancement. Skills training programs that incorporate active thinking, practice and feedback have been proven to successfully drive transfer to practice.

Elements of Effective Skills-based Training

Skills-based training focuses on teaching a specific task with the goal of the learner being immediately able to perform it. Students have ownership of their learning, which is designed to help bridge gaps in understanding. Because of the focus on synthesis, evaluation and application of new skills, skills-based learning sparks resourcefulness and critical thinking.

Activity designs for skills-based training can take many forms, using technologically advanced features like adaptive learning or simulation or more low-tech elements such as role-play and question-and-answer sessions. Training on soft skills, such as communication, cross-cultural training and interpersonal skills, can often employ the same mechanisms, including practice and delivering feedback.

Regardless of the mechanism, the instructional design of the activity has the greatest impact on skills development. Simply put, if we want learners to gain certain skills, we need to explain exactly what we want them to learn and give them opportunities to practice those skills. The quality and frequency with which we customize activity content, methods and/or format to learners’ needs, using or invoking realistic settings, as well as the frequency of demonstration and reflective practice all affect engagement, recall and skills learning.

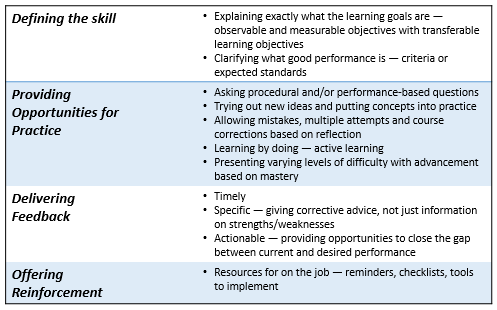

Effective skills-based training includes four key elements within the activity:

Teaching soft skills may require some creative content development to facilitate new behaviors, provide practice and deliver feedback. Perhaps an activity could show video clips and ask learners to identify and evaluate how well specified communication skills are executed. A diverse faculty could model inclusion, or learners could practice difficult conversations with role-play. Case studies and even test questions could include reminders on the importance of a specific foundational skill. Real-world examples make the lesson more relevant.

Skills Assessment

Valid measures of clinical behavior are of fundamental importance to accurately identify gaps in care delivery, enable continuous improvement of quality of care and, ultimately, provide improved patient care. Confirming the successful acquisition of a skill requires the demonstration of proficiency of the skill, and the performance of a clinical skill must be observable.

Assessment questions (i.e., procedural and/or performance) aligned with the learning objectives and content of the activity allow learners to put their newly acquired skills into action. Standardized clinical vignettes are a simple, time-efficient, and valid tool for assessing competence. Performance on clinical vignettes correlated significantly with standardized patient-based assessments, indicating they serve well as a proxy for clinical practice.4

The typical instruments of outcomes data collection, however, yield limited insight on where competence gaps may still lie, which in turn may limit the provider’s ability to effect change.

Quantitative assessments allow learners to demonstrate understanding by responding to knowledge-based questions and demonstrate proficiency with responses to questions stemming from clinical case vignettes yet don’t provide information on the learner’s thinking process. Qualitative feedback tools provide insight into learners’ thinking process but are often disconnected from competence assessments and, therefore, fall short of capturing clinical reasoning.

These limitations can be addressed with a two-pronged outcomes assessment combining clinical case vignettes and open-ended feedback instruments, where learners are asked to make decisions, then explain their choices. Since clinicians justify their decisions in their own words, the rationales for incorrect responses can be explored, allowing educators to understand the basis for the choices and discern the reasons for remaining gaps. Ultimately, by measuring both clinicians’ decisions and the rationale behind them, the two assessments provide a much richer analysis of clinician skill acquisition than can be shown with a single, standard outcomes method5.

We can also use confidence-based assessment to enhance typical outcomes data, further deepening skill acquisition assessment. Research has shown that the connection of knowledge and confidence provides an acceleration of learning and empowers people to act.6 People who are confidently correct will take actions that are productive.

Assessing Soft Skills

Measuring soft skills informed by activity-based testing alone can create a problem for metrics. Additional assessments may also need to be considered to measure for soft skill improvement. For example, in the blended approach described above, soft skills improvement can be measured by evaluating a learner’s self-awareness and reflection capabilities in the open- ended decision explanations. Other evaluations could include answering questions based on a video demonstration or using questionnaires or short essays in a self-assessment. Regardless of the assessment type used, specific baseline proficiencies, relevant to your definition of the skill and easily measurable, need to be outlined at the onset of the activity development.

In summary, developing effective skills-based training and valid assessments for both hard and soft skills will result in educational programs that will close gaps in care delivery, provide continuous improvement of quality of care and, ultimately, improve patient care.

References

- Densen P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2011;122:48-58. PMID: 21686208; PMCID: PMC3116346.

- Torres, Christiana, Skills and Competencies: What’s the Difference? December 15, 2021. https://blog.degreed.com/skills-and-competencies/

- Indeed Editorial Team, Skills Every Doctor Needs: Definition and Examples, January 22, 2021

https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/resumes-cover-letters/skills-of-a-doctor

- Sowden, Gillian & Vestal, Heather & Stoklosa, Joseph & Valcourt, Stephanie & Peabody, John & Keary, Christopher & Nejad, Shamim & Caminis, Argyro & Huffman, Jeff. (2016). Clinical Case Vignettes: A Promising Tool to Assess Competence in the Management of Agitation. Academic Psychiatry. 41. 10.1007/s40596-016-0604-1.

- Whitepaper, Novel Competence Assessment Yields Greater Potential to Effect Change in Healthcare. PeerView Institute for Medical Education, March, 2022.

- Confidence-based learning. Psychology Wiki, https://psychology.fandom.com/wiki/Confidence-based_learning

Resources

Calibre Institute for Quality Medical Education https://ciqme.com/

Connolly, Fergal. Evidence-Based Design That Leads to Learning Transfer, November 16, 2020 https://www.td.org/insights/evidence-based-design-that-leads-to-learning-transfer

15 Tips for Teaching Soft Skills Online or in the Classroom https://www.realityworks.com/blog/15-tips- for-teaching-soft-skills-online-or-in-the-classroom/

Hrisos S, Eccles MP, Francis JJ, Dickinson HO, Kaner EF, Beyer F, Johnston M. Are there valid proxy measures of clinical behaviour? A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2009 Jul 3;4:37. doi: 10.1186/1748- 5908-4-37. PMID: 19575790; PMCID: PMC2713194.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2713194/

Malamed, Connie. How To Increase Learning Transfer. https://theelearningcoach.com/elearning_design/transfer-of-learning/

Peabody JW, Tozija F, Muñoz JA, Nordyke RJ, Luck J. Using vignettes to compare the quality of clinical care variation in economically divergent countries. Health Serv Res. 2004 Dec;39(6 Pt 2):1951-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00327.x. PMID: 15544639; PMCID: PMC1361107.

Shank, Patti. Can They Do It in the Real World? Designing for Transfer of Learning September 07, 2004 https://learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/288/can-they-do-it-in-the-real-world-designing-for-transfer-of- learning

Skill-based Instruction https://www.literacyta.com/skill-based-instruction

Sowden, Gillian & Vestal, Heather & Stoklosa, Joseph & Valcourt, Stephanie & Peabody, John & Keary, Christopher & Nejad, Shamim & Caminis, Argyro & Huffman, Jeff. (2016). Clinical Case Vignettes: A Promising Tool to Assess Competence in the Management of Agitation. Academic Psychiatry. 41.

10.1007/s40596-016-0604-1.

Torres, Christiana, Skills and Competencies: What’s the Difference? December 15, 2021. https://blog.degreed.com/skills-and-competencies/

Heather Drew is the director of education strategy at PVI, PeerView Institute for Medical Education, where she leads product and engagement initiatives to meet defined strategic needs. Heather has nearly 20 years’ experience in medical education with leadership roles in strategic planning, marketing, and product management, and has trained with the CALIBRE Institute for Quality Medical Education in instructional design.