Driving learner participation is a constant goal for every educator who creates medical education activities. For providers of online, on-demand education, success is often measured by the volume of clinicians participating instead of changes in knowledge, competence or performance. This approach can often lead to unrealistic expectations of providers, reporting inflated participation numbers. For example, some report page views of the overview page of the activity, instead of measuring clinicians who actually engaged with the content of the education, which is the most effective way of assessing improvements in clinician knowledge, competence, confidence and practice change. There can also be pressure to look at all learners as being the same, painting all with the same brush, when assessing curriculums. But they are all uniquely different based on numerous demographics including profession, specialty, years in practice, practice location and patient population that they treat. Recruiting the right learner into the educational initiative means focusing on the appropriate demographics and understanding which group of clinicians has demonstrated a need for the activity. When assessing the outcomes of the education, providers should dive deeper than lumping all clinicians together, by segmenting learner groups in order to clearly measure the impact that the education might have on clinician knowledge, competence, confidence and practice change.

Identifying the Right Learner

In the U.S., there are just over 1 million physicians practicing in more than 135 medical specialties and subspecialties

in more than 135 medical specialties and subspecialties . Each of these clinicians might see a unique blend of patients, categorized not only by disease or condition, but by the patient’s own demographics and various social determinants of health, which can significantly impact the practice of the clinician. With such a large pool of potential learners, the ability to recognize that not all learners are going to be impacted by educational efforts becomes paramount when designing interventions.

. Each of these clinicians might see a unique blend of patients, categorized not only by disease or condition, but by the patient’s own demographics and various social determinants of health, which can significantly impact the practice of the clinician. With such a large pool of potential learners, the ability to recognize that not all learners are going to be impacted by educational efforts becomes paramount when designing interventions.

Efforts to recruit learners to online, on-demand CME activities should be focused on the targeted learner group that will benefit from the educational activity, not a broad approach that might recruit learners who do not need the education or treating learner needs like a commodity that is the same across all specialties.

There are numerous questions that should be asked when targeting a specific clinician group, but a few key questions that should always be asked include:

- Are the learners of the right profession (i.e., physician, NP, PA or nurse) for the education?

- Are they the right specialty for the topics being taught? Often a broad approach is taken instead of looking at learner groups including specialists with a more targeted approach. For example, if the topic is adamantinoma, will all oncologists need the education, or does the needs assessment identify a specific pool of treaters?

- Is there a specific geographical element to the needs assessment that should be considered, targeting specific regions or states? Is the condition more prevalent in a particular area of the country?

- Are they seeing patients that fit the need for the education, or are they retired and not seeing patients at all?

- Is the outcomes pool size anticipated realistically aligned with the size of the specialty to measure successful outcomes?

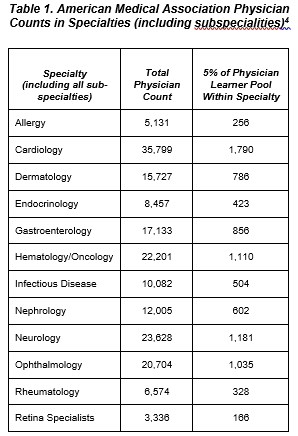

When setting realistic recruitment goals, the potential size of the learner group must be taken into consideration, as well as other factors within their profession and specialty, all driven by the needs assessment. While a common goal may be 1,000 learners participating in an online, on-demand activity, if there are only 4,000 clinicians in the universe of those practicing within the targeted group, the chances of achieving the learner goal is limited from the start. Also, recognizing the importance of the educational topic with the learners who treat a specific patient population is crucial. Consider cholangiocarcinoma, a rare cancer that develops in the bile ducts of the liver. An estimated 8,000 cases are diagnosed per year in the United States. Even though liver malignancies are treated by oncologists who specialize in gastrointestinal cancer, is it reasonable to assume all gastrointestinal cancer specialists would be equipped to treat someone with this tumor type given how uncommon it is? For such rare diseases, is 1,000 learners for outcomes a realistic expectation?

When setting realistic recruitment goals, the potential size of the learner group must be taken into consideration, as well as other factors within their profession and specialty, all driven by the needs assessment. While a common goal may be 1,000 learners participating in an online, on-demand activity, if there are only 4,000 clinicians in the universe of those practicing within the targeted group, the chances of achieving the learner goal is limited from the start. Also, recognizing the importance of the educational topic with the learners who treat a specific patient population is crucial. Consider cholangiocarcinoma, a rare cancer that develops in the bile ducts of the liver. An estimated 8,000 cases are diagnosed per year in the United States. Even though liver malignancies are treated by oncologists who specialize in gastrointestinal cancer, is it reasonable to assume all gastrointestinal cancer specialists would be equipped to treat someone with this tumor type given how uncommon it is? For such rare diseases, is 1,000 learners for outcomes a realistic expectation?

Overwhelmed and Burned Out

A number of professions are facing a declining shortage of specialists available for growing diseases, with the Association of American Medical Colleges estimating a shortage between 54,100 and 139,000 physicians in both primary and specialty care by 2023. According to the findings of the report, shortages are caused by patient population growth, people living longer and demanding more care, changes in retirement patterns and overall physician burnoutt.

In a specialty where the amount of available practicing specialists is low, this shortage may have an even greater impact on engagement patterns. In the U.S., there are approximately 6,574 practicing rheumatologists seeing a growing population of patients with rheumatic diseases, and that patient population is expected to continue to grow at a rate higher than available care.5 “By 2040, the number of United States (U.S.) adults diagnosed with arthritis is projected to increase by 49%, to 78.4 million.”5

practicing rheumatologists seeing a growing population of patients with rheumatic diseases, and that patient population is expected to continue to grow at a rate higher than available care.5 “By 2040, the number of United States (U.S.) adults diagnosed with arthritis is projected to increase by 49%, to 78.4 million.”5

The need for education clearly exists to support this and other professions, but is it realistic to expect that 10% of an overwhelmed, small population of specialists will engage with every available online, on-demand CME activity? What should be the recruitment and educational design goals for a specialty such as rheumatology? If the shortage of support and resources facing healthcare practitioners exists, how can education providers work to better understand individual specialty needs and work to create better educational goals specific to those needs?

The solution that many providers turn to when attempting to achieve their often unrealistic targeted recruitment goals is to add in other professions, such as primary care, to hit outcomes targets. This approach can lead to assessment data that is clouded by learners who do not see the right patients. The proper solution may be to re-evaluate the educational recruitment goals and set the right expectation for learner participation.

Assessing the Impact of the Education

Before starting to consider the assessment of online, on-demand educational efforts, there needs to be a clear definition of what a learner is and what they are not. Using the Outcomes Standardization Project published definitions, a learner is someone who “starts the core educational content” and does not include participants who simply visit an overview page or perhaps only complete the pre-test. The clinician must begin the core content, engaging with the education, to be considered a learner. Setting this expectation with stakeholders who are evaluating or supporting the education is crucial to setting clear goals about learner participation and engagement.

published definitions, a learner is someone who “starts the core educational content” and does not include participants who simply visit an overview page or perhaps only complete the pre-test. The clinician must begin the core content, engaging with the education, to be considered a learner. Setting this expectation with stakeholders who are evaluating or supporting the education is crucial to setting clear goals about learner participation and engagement.

Once we have a clear definition of a learner, we are ready to take the next step and categorize learners into sub-groups to better measure the impact of the education. Assessment of education should initially look to break down the target learners from all others who participated in the education, which will provide a clearer picture of gains in knowledge, competence, confidence, and practice change.

The next step in the assessment process is to breakdown the targeted learners even further, measuring engagement with the education, identifying those who were truly there to learn. Consider breaking targeted learners down into four cohorts: super learners, passive or general learners, narrow-focused learners and certificate seekers. Each group has several distinct characteristics that delineates them, including key measures of how much content they consumed, how they engaged with additional resources, did they answer all questions, or did they just skip to the end, take the post-test and get their CME certificate?

Further Defining Learner Cohorts

Super learners: This group of learners dives deeper into the education than many of their peers. Super learners will not only watch all of the content, but they often rewatch sections, scrubbing back and forth to review key portions of the content. These learners will also answer all of the questions within the activity, including free-text reflective questions, and are more likely to take time reviewing supporting resources or portions of the activity if they failed the post-test. They will consistently engage with the content on a deeper level: taking notes, viewing and downloading resources and pinning content for future reference. It should be noted that while these learners are the ideal, they are often a small percentage of the overall number of learners.

Passive or general learners: Typically, a bigger percentage of an activity’s learner population is classified as passive or general learners. These learners will consume all the content but engage more superficially than the super learners. They might answer some of the intra-activity questions, but typically do not engage with more in-depth questions such as reflective or multi-model questions. This group does take notes, often ignores supporting resources, and rarely revisits and activity once completed.

Narrow-focus learners: This group of learners is typically engaging with the activity to answer a specific clinical question. These learners will engage with the content, and often exit the education once they have found the answer to their question. Narrow-focused learners will view and download supporting resources if they are related to their original purpose of engaging with the education — finding an answer to a specific clinical question. The majority of these learners do not complete the required post-test and evaluation in order to claim credit.

Certificate seekers: The final group of learners are those learners who are only seeking credit — the education may not even be related to their clinical practice. Learners who self-identified as only participating because of the CME credit can be up to 22% of the audience. This group will often consume a small percentage of the educational content, skipping over large sections or all of the education to get to the end, take the post-test, and complete the evaluation to secure credit. These learners can be detrimental when measuring the effectiveness of the education as they might take post-tests numerous times, guessing their way through the questions until they pass the test. When possible, certificate seekers’ data should be removed from pre/post assessments and other outcomes measures. Designing and recruiting learners specific to the education, as discussed, may cut down on the amount of certificate seekers.

All stakeholders within CME and CPD should strive for realistic goals when estimating the impact of online, on-demand educational interventions, measuring true participation and not overstating learner numbers. As a community, we are all facing the need to measure and show impact of the educational interventions for which we design. Making sure that, as education providers, we take time to clearly understand which clinicians have been identified by the needs assessment as targets for the education before establishing program goals and objectives is what will help deliver the best education. When assessing the impact of the education, we need to better understand that not all learners are created equal, that learner sub-groups exist and can significantly impact the quality of our outcomes data including the assessment of knowledge, competence, confidence and practice change, as well as identifying persistent gaps and the need for additional interventions.

U.S. physicians–statistics & facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/1244/physicians/#dossierKeyfigures Statistica. Last accessed 9/20/22.

U.S. physicians–statistics & facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/1244/physicians/#dossierKeyfigures Statistica. Last accessed 9/20/22.

https://www.aamc.org/cim/explore-options/specialty-profiles

https://www.aamc.org/cim/explore-options/specialty-profiles

New AAMC Report Confirms Growing Physician Shortage; AAMC; https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/new-aamc-report-confirms-growing-physician-shortage. June 26, 2020. Last accessed September 20, 2022.

New AAMC Report Confirms Growing Physician Shortage; AAMC; https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/new-aamc-report-confirms-growing-physician-shortage. June 26, 2020. Last accessed September 20, 2022.

Medical Marketing Services. American Medical Association Physician list. Updated August, 1, 2022. Accessed September 22, 2022 https://insp01.blob.core.windows.net/public/pdf/AMA_SpecialtyByTops.pdf

Medical Marketing Services. American Medical Association Physician list. Updated August, 1, 2022. Accessed September 22, 2022 https://insp01.blob.core.windows.net/public/pdf/AMA_SpecialtyByTops.pdf

Brian S. McGowan, Anthia Mandarakas, Sue McGuinness, Jason Olivieri, Karyn Ruiz-Cordell, Greg Salinas & Wendy Turell (2020) Outcomes Standardisation Project (OSP) for Continuing Medical Education (CE/CME) Professionals: Background, Methods, and Initial Terms and Definitions, Journal of European CME, 9:1, 1717187, DOI: 10.1080/21614083.2020.1717187

Brian S. McGowan, Anthia Mandarakas, Sue McGuinness, Jason Olivieri, Karyn Ruiz-Cordell, Greg Salinas & Wendy Turell (2020) Outcomes Standardisation Project (OSP) for Continuing Medical Education (CE/CME) Professionals: Background, Methods, and Initial Terms and Definitions, Journal of European CME, 9:1, 1717187, DOI: 10.1080/21614083.2020.1717187