Introduction

Numbers make sense. They are easily plugged into data analysis software, resulting in percentages, frequencies, ratings and ranks. Quantitative research findings reveal trends and tendencies, and they sometimes help us predict and adapt. They tell us “what” has happened or is happening. But how do we know “why” or “how” it is occurring? To answer these questions, data that reflect stakeholders' experiences, perceptions and feelings may be more helpful. These qualitative data are often spoken words, text, recordings, transcripts or journal and field notes from observations that cannot be analyzed using traditional statistical procedures. However, they are vital in helping us make sense of phenomena and interpret meanings, answering the “why” and “how” questions. Reporting qualitative findings usually includes an interpretation of a phenomenon through analysis of study participants’ voices. Are we hearing them?

Qualitative research is valuable for investigating the meaning humans attribute to a social or individual problem. It is exploratory, utilizing semi-structured, open-ended, interactive, reflective inquiries, allowing participants to reflect on their prior experiences. In the case of CPD learners, they are able to reflect on prior learning, as well as past, current, and planned behaviors and practices. Qualitative researchers gain keen insight into stakeholders’ viewpoints; therefore, issues can be identified which may have been missed by quantitative investigations (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Data are analyzed through inductive frameworks to identify broad emergent themes from specific participant input. Although various methods exist, the process of qualitative data analysis includes the following sequential steps, advancing from specific to general:

- Organize the data and prepare for analysis.

- Read through all of the data several times.

- Begin the process of coding data, organizing similar data into groups or categories and labeling them with a word or phrase.

- Develop descriptions and identify emerging themes.

- Select quotes or other representative data to support the identified themes when writing the narrative report of findings.

Qualitative health research involves collecting data in natural settings and analyzing them inductively to identify emerging patterns or themes. Qualitative skeptics may suggest a lack of replicability, reliability and validity. However, qualitative researchers ensure trustworthiness, transparency and rigor through systematic data collection and analysis methods. They often pilot the data collection tool before study initiation and revise it if needed. Reflective journaling and utilizing a note-taker and peer-coder help ensure ethical qualitative research. Measures are in place to ensure confidentiality, and member checking is conducted, allowing participants to review findings and offer input.

Qualitative Research and the CPD Professional

While qualitative health research has proven valuable in many areas such as explaining quantitative data, patient-reported outcomes, and investigating patient and family involvement in care (Jafarpoor et al., 2019; Mejdahl et al., 2020; Safdar et al., 2016; Verhoef et al., 2002), it has utility for the continuing professional development (CPD) of health professionals. Qualitative research is beneficial for identifying learner needs and evaluating program and learner outcomes through well-grounded, rich descriptions of human experiences and perceptions.

Included in the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) CE Educator's Toolkit (ACCME, 2022) is a list of suggested methods for collecting needs assessment data. Focus groups, key informant feedback, one-on-one interviews and formal or informal meetings with colleagues are suggested methods of determining perceived needs. For determining unperceived needs, interviews/focus groups with experts in the field, input from patients through interviews or focus groups and patients as members of planning committees are suggested, as well as direct observation of practice performance. Each of these suggests collecting and analyzing qualitative data, which are the voices or observed behavior of our learners, patients and other stakeholders.

For outcomes assessment, the same ACCME toolkit lists semi-structured interviews, learner feedback/debriefing at the end of a session and observation data to assess outcomes. These also reflect qualitative methods. These data can help us understand the learner experience during and after the activity and changes in practice or behavior.

Qualitative Research in Action: The Case of Maria

Maria Martin is the director of continuing education for health professionals at a large academic medical center. She arranged a meeting with the OB/GYN department providers and staff to plan their annual continuing education conference scheduled for nine months away. Maria initiated the meeting with a reminder that documented learner needs must support the conference's educational content and asked if the team could share departmental outcomes, comparison data or observations to jumpstart conference planning.

- The nurse planner mentioned that OB/GYN HCAHPS scores had declined over the past year, specifically on measures of provider communication with the patient.

- While Maria was taking notes, a physician on the committee reported declining health outcomes for patients with BMI scores over 30, which is significant, as the medical center is located in a state with an obesity rate of almost 40%.

- One of the physician planners then admitted her hesitance to initiate a conversation with her patients about weight management and nutrition because she had previously received adverse reactions from patients and their families when she broached the topic.

As an experienced CPD professional and qualitative researcher, Maria knew that the touchstone of an individual's own experience could be valuable in explaining scores and ratings. The perceptions of patients could answer the “why” and “how” of the “what” data reported by the committee. Remembering that the department sponsored a monthly support/informational group for their expecting and new moms, Maria asked and was granted permission to attend the next session. She formulated research questions to explore with a patient focus group consisting of support group participants conveniently gathered. These were:

1. What are OB/GYN patients' experiences with and perceptions of provider communication regarding weight management and BMI?

2. How can their experiences help explain or elucidate department HCAHPS scores and patient outcomes?

Maria conducted the focus group using a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions and recorded the discussion. Afterward, she downloaded the recording transcript and began organizing raw data in preparation for the coding process. She coded the data, then categorized coded data and labeled categories. Overarching, broad themes were identified, and Maria selected salient participant quotes to support the themes. An experienced qualitative researcher in a nearby office served as her peer coder. After he coded the data independently, he and Maria collaborated and agreed on the data coding and emergent themes.

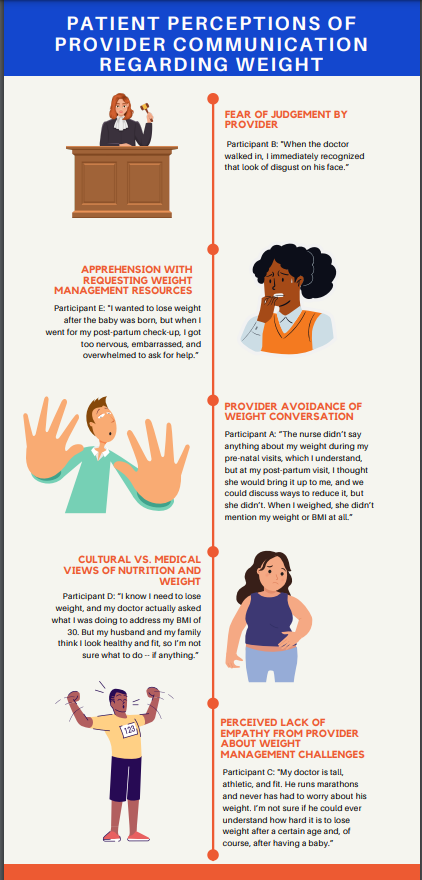

At the next OB/GYN planning meeting, Maria presented her focus group findings with supporting quotes and developed an infographic for data visualization (see Figure 1). After a lively discussion about the impact of provider/patient interaction on satisfaction scores and outcomes, the group then discussed a lack of obesity training in the formal curricula in schools of health professions. Maria and her planners then determined the focus of their conference — interpersonal communication between providers and patients. Specific sessions on obesity training, motivational interviewing, implicit bias and patient coaching would be offered. Objectives for the conference included increased knowledge levels regarding the complexity and physiologic basis for obesity, decreased negative attitudes toward patients with obesity through an implicit bias module, and further developed skills in motivational interviewing and coaching. Maria planned to use a similar qualitative approach for outcomes assessment and add one-on-one interviews with OB/GYN providers and staff to discuss planned and realized practice changes.

Summary

Qualitative health research explores health and illness through the lens of the patient rather than the researcher, documenting emotions, beliefs, behaviors, values, and responses to experiences. The same investigative process can be applied to determining the needs and outcomes of clinicians and other health professionals in the continuing professional development continuum. Morse (2012) maintains that the most important reason for conducting qualitative research in the healthcare context is the advancement of social justice and humanizing care. This should also be a significant focus for healthcare CPD professionals as we purpose to provide learning experiences aimed at the individual needs and outcomes of learners, determined through interaction, conversation or observation. In order to hear the voices of our stakeholders, we must listen.

Figure 1. Themes emerging from the qualitative investigation, with supporting participant quotes.

References

Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. 2022. CE Educator’s Toolkit: Evidence-based design and implementation strategies for effective continuing education. http://www.accme.org/ceeducatorstoolkit

Creswell, J.W.& Creswell, J.D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Jafarpoor, H., Vasli, P. & Manoochehri, H. (2020). How is family involved in clinical care and decision-making in intensive care units? A qualitative study. Contemporary Nurse, 56:3, 215-229, DOI: 10.1080/10376178.2020.1801350

Mejdahl, C. T., Schougaard, L., Hjollund, N. H., Riiskjær, E., & Lomborg, K. (2020). Patient-reported outcome measures in the interaction between patient and clinician - a multi-perspective qualitative study. Journal of patient-reported outcomes, 4(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-019-0170-x

Morse, J.M. (2012). Qualitative health research: Creating a new discipline (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315421650

Safdar, N., Abbo, L., Knobloch, M., & Seo, S. (2016). Research methods in healthcare epidemiology: Survey and qualitative research. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 37(11), 1272-1277. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.171

Verhoef, M.J., Casebeer, A.L., & Hilsden, R. J. (2002). Assessing efficacy of complementary medicine: Adding qualitative research methods to the “gold standard.” Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 8(3), 275-281.

Key Concepts

- Qualitative research answers the “why” and “how” question when quantitative data may only tell us “what.”

- It allows for further insight and understanding of complex, ambiguous, or nuanced situations.

- Qualitative data can be collected in a variety of ways, many of which can be accomplished during planning or follow-up meetings, patients groups, or behavior observations.

- Measures to ensure transparency, rigor, and trustworthiness during qualitative research must be utilized, but are not complex.

- Researcher reflexivity and transparency is key throughout the data collection and analysis process.

- Through qualitative research, CPD professionals can gain profound insight into a problem or gap by exploring the experiences, opinions, feelings, motivations, and behaviors of participants -- but we must listen.