|

Editor’s Note: This is the first article of a 2-part series about a gender-affirming continuing education (CE)/continuing medical education (CME) initiative for healthcare professionals. This article addresses the planning and design of the educational initiative. The second article will discuss the impact of the education in addition to a new evaluation methodology to measure the effect of attitudinal, behavioral, and cultural shifts on clinical skills and practice change.

|

Although transgender and gender-nonconforming (TGNC) issues have recently moved to the forefront of popular culture, the legal system, and world news, the U.S. healthcare system continues to struggle with understanding and providing the best care for this underserved, at-risk population.

Background

In January 2015, the Annenberg Center for Health Sciences at Eisenhower (Annenberg Center) coordinated with its parent company, Eisenhower Medical Center, to hold a CE/CME-certified meeting focused exclusively on TGNC healthcare issues. Conducted on the Eisenhower Medical Center campus, this half-day meeting included presentations from national experts on TGNC primary care issues, healthcare needs of TGNC adolescents, health disparities, and gender-affirmation healthcare. Attendees included 41 healthcare professionals plus members of the local TGNC community. Based on the success of this meeting, the Annenberg Center began to explore additional opportunities to bring TGNC healthcare education to a broader, national audience.

Educating the Educator

As we began our exploration, leadership observed team members exhibiting common cultural insensitivities that underlie the healthcare disparities the initiative was intended to mitigate. We recognized that the successful development of a broad, culturally competent, gender-affirming educational initiative to reduce TGNC healthcare disparities would be bolstered by improving our own competency and literacy in gender expression.

In February 2016, Annenberg Center team members who were already proficient at navigating TGNC healthcare issues developed a two-hour training program that focused on human sexuality, gender expression and culturally competent healthcare. The entire Annenberg Center staff participated in this training.

A component of the training program involved inducing cognitive dissonance to create an awareness of the challenges TGNC patients report in their interactions with the healthcare system.

For example: the National Center for Transgender Equality’s 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey ― the largest survey focused on the experiences of TGNC persons living in the United States ― found that that one-third of its 27,715 respondents had at least one negative healthcare encounter within the prior year owing to their TGNC identity.

These encounters ranged from care that was culturally insensitive to verbal harassment and even physical abuse.

The survey showed that 23 percent of respondents purposefully did not seek out medical attention in the past year — even when needed — for fear of mistreatment.

When these facts were provided to the staff dedicated educating healthcare professionals and improving patient outcomes, it challenged existing dogma and helped open minds.

Because language is a substantial element of culture, the internal training program reviewed terminologies such as “gender identity” and “gender expression.” Staff members received training on how appropriate pronoun usage contributes to a TGNC person feeling validated and welcomed. The team brainstormed healthcare scenarios in which “privilege” ― i.e., the idea that there are some things in life that you will never have to think about, experience, or explain just because of who you are ― can contribute to cultural insensitivities and negatively affect a TGNC person’s healthcare experience. At the conclusion of the program, all Annenberg Center staff reported being better able to identify the healthcare challenges that TGNC persons experience and being better able to employ best practices for positive, culturally sensitive interactions with TGNC people.

Plan Backwards, Implement Forwards

With its internal staff training complete, we began conceptualizing a pilot program for broader CE/CME-certified educational interventions. In order to better understand TGNC health disparities, we analyzed data from past CE/CME activities, surveyed healthcare professionals involved in primary care and/or HIV care, held conversations with previous faculty and national experts in HIV and/or TGNC healthcare, and performed an extensive search of medical literature.

We decided to target specialty HIV care team members with a pilot program that incorporated several findings and priorities, including:

- In July 2015, the U.S. Office of National AIDS Policy added three new priorities for national monitoring purposes ― i.e., PrEP, stigma, HIV among TGNC persons ― with calls for the implementation of “innovative and culturally appropriate models” to improve the access to and retention in care for TGNC patients.

- TGNC people are more likely to take pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) if it is made available to them by healthcare professionals who are experienced in working with the TGNC community.

- The percentage of black or African American transgender women living with HIV ranges from 19% to 30% (vs 0.3% of all American adults).

- Practices that integrated HIV care with overall TGNC-related and/or transition-related healthcare needs have higher rates of HIV-care retention and treatment adherence.

- Adherence rates to antiretroviral therapy can be negatively affected if TGNC patients feel that they need to choose between antiretroviral therapy and hormone therapy for any reasons (eg, financial reasons, healthcare professional’s recommendations).

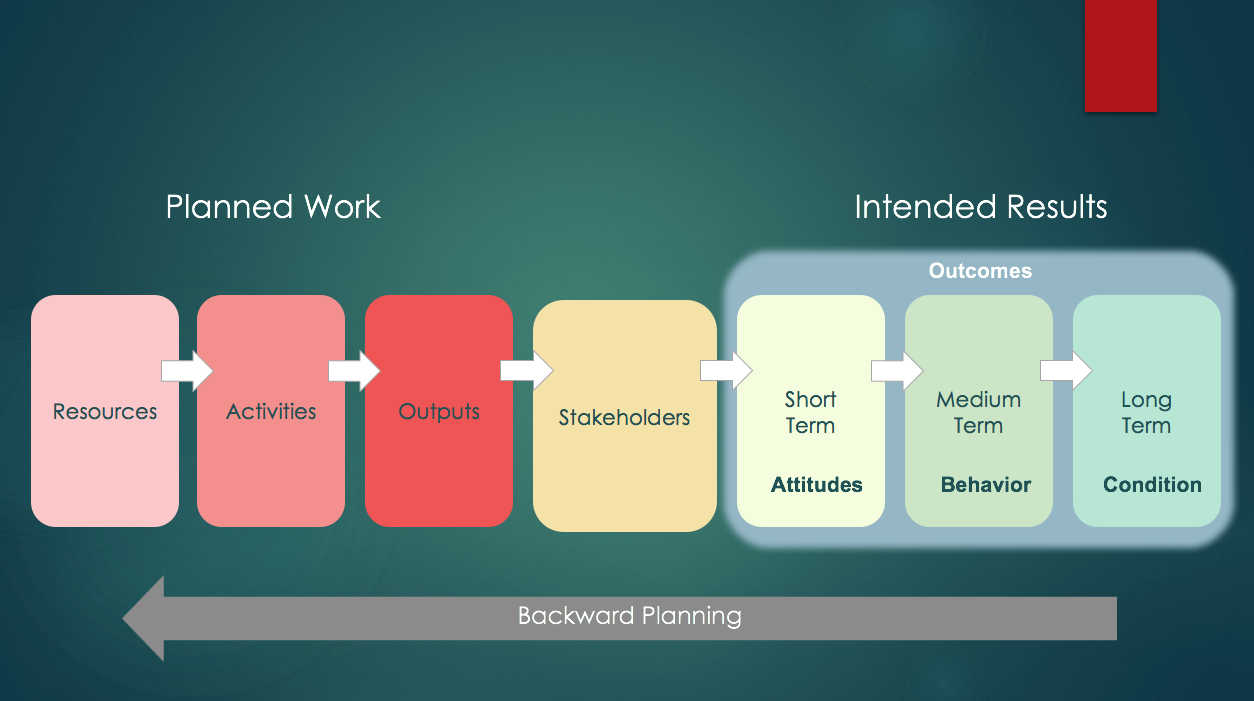

We utilized a logic model to guide the educational-design process (Figure 1); the model helps to define five critical components:

- resources (what is needed to support the education);

- activities (the resource-utilization plan);

- outputs (what is delivered/produced);

- stakeholders (who must be reached; ie, learners, patients); and

- intended results (what is expected for changes in knowledge, skills, attitudes, behavior, and population impact).

Using backwards planning, we first evaluated intended results for the pilot program, followed by which stakeholders needed to be reached, what program outputs would be delivered, the activities best suited for delivery, and the resources required.

Intended Results

In designing an educational initiative for gender-affirming cultural competency in HIV care, we identified several desired short- and medium-term outcomes, including:

- HIV and infectious disease specialists actively engaging with TGNC patients in a culturally competent and culturally sensitive manner;

- HIV and infectious disease specialists seeking opportunities to better link and retain TGNC patients in HIV care by providing care that aligns with best practices in gender-affirmation healthcare;

- TGNC patients receiving HIV-prevention strategies and education that better align with gender identity and TGNC culture; and

- TGNC patients receiving culturally competent and culturally sensitive HIV care that is tailored to their overall healthcare needs and expectations.

To achieve these desired outcomes, Annenberg Center recognized that healthcare professionals involved in HIV care would need an improved ability to:

- incorporate gender-affirmation healthcare terminologies and support strategies into practice;

- educate patients on HIV prevention and care that is respectful and specific to transgender patients;

- engage and retain HIV-infected transgender patients in the continuum of care; and

- identify and address barriers to treatment adherence specific to HIV-infected transgender patients.

Stakeholders

Although the education was targeted to HIV specialists, infectious disease physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants at participating host sites, we encouraged host sites to invite faculty and staff from nearby academic institutions as well as clinicians from local community hospitals and group practices. It was further determined that the information would be relevant to other HIV care team members who interact with patients (e.g., social workers, nutritionists/dietitians); as such, invitations were extended to these care team members.

Outputs

The format for each live meeting was established as an interactive, multidisciplinary group setting. In addition to a didactic presentation, speaking faculty introduced and discussed 2 case scenarios. Learners at participating host sites were encouraged to bring questions and their own clinical cases (if applicable) for group or individualized discussion. The activity allotted for ample opportunity to exchange ideas and viewpoints, with faculty engaging in one-on-one interactions at the conclusion of each meeting.

Activities

With a focus on the specialty HIV care team, we chose to target academic and community hospital-affiliated infectious disease departments as well as smaller HIV community clinics. Host-site inclusion criteria were further narrowed to geographic areas with larger local TGNC communities. Data on local TGNC communities were scarce, which was expected since TGNC persons may chose not to self-identify for fear of social stigma, discrimination, economic marginalization, and victimization. We reviewed national and state population data specific to TGNC communities, as well as national, state, and local data on broader LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning or queer) communities. We excluded cities where LGBTQ-focused institutions indicated that they were already working within the local healthcare communities to support gender-affirming care (e.g., Boston and San Francisco).

Resources

For this pilot program to be successful, it needed content-development and speaking faculty with specific expertise. Faculty-selection criteria included medical/editorial boards for TGNC healthcare associations and publications, subject matter experts with experience speaking at national and international LGBTQ conferences, authors of peer-reviewed articles on HIV care for the TGNC community, and leading or co-investigators for clinical trials or federally funded studies.

Lastly, we discussed potential opportunities for independent medical education grant support for this pilot program. We identified commercial supporters with a therapeutic interest in HIV care, and developed grant request proposals for their consideration.

National Launch of Gender-Affirmation Education for Specialty HIV Care Teams

In May 2016, we launched a 7-part, CE/CME-certified series of live activities on gender-affirmation healthcare titled “Experts in Residence: HIV Care for Transgender Patients.” The initiative was supported by independent educational grants from Janssen Therapeutics, Division of Janssen Products, LP and ViiV Healthcare.

We collaborated on the content development of the CE/CME interventions with 3 renowned experts affiliated with Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Chase Brexton Health Care; each also served as speaking faculty. The peer reviewer for the initiative was also an expert in HIV care for sexual and gender minorities.

Outcomes and Impact

Seven live meetings were held in 5 different states ― i.e., California, Florida, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and New York. The host sites included 5 community hospitals, 1 academic medical center, and 1 community HIV clinic. For the total series, we reached 229 learners ― an average of 33 learners per site ― which exceeded the original participation goal by 31%. The largest meeting in the series was held at the community HIV clinic; the clinic is part of a large county health agency that advertised the CE/CME-certified meeting to its entire system, with some of the 60 learners at that meeting traveling upwards of 1 hour to attend. Figure 2 captures the overall impact of the 7 live meetings. (Editor’s Note: Additional data reporting, as well as the outcomes methodology developed and we used for this initiative, will be discussed in the second part of this article series.)

In addition to the quantitative data, there is a considerable amount of anecdotal evidence on the impact that this initiative had on learners. For example, after one of the live meetings, a learner approached our staff and self-identified as a transgender person. The learner praised the speaker and presentation, and thanked our staff for helping to educate colleagues on TGNC healthcare issues in a culturally sensitive manner, citing a “huge need” for gender-affirmation education in the learner’s city.

Furthermore, although the pilot program was not originally intended to impact an overall healthcare system, it may have done just that. Weeks after hosting a meeting, one of the community hospital sites contacted us inquiring as to whether it would be possible to invite our faculty back to conduct additional training for the entire hospital staff. We helped the hospital get in touch with the original faculty speaker to coordinate additional visits and training sessions.

Conclusion

Designing culturally competent, gender-affirming education for healthcare professionals requires cultural sensitivity and careful planning. Using a logic model and backward planning, we were able to develop highly targeted educational interventions to effectively engage HIV care teams and improve their gender-affirming knowledge, skills, and practice competencies. Another important contribution and outcome was an improved cultural competence among our staff; this heightened our understanding of the educational need and challenge, improved the effectiveness of our work with faculty and intervention sites, created a more welcoming work environment, and reaffirmed our commitment to innovative professional development.

ELEVATE-ing Medical Education to Transform Healthcare Environments

In June 2018, Annenberg Center will launch phase II of its gender-affirmation educational initiative. “ELEVATE: Your Gender-Affirming Healthcare Environment for Optimal HIV Care” is a nationwide gender-affirmation healthcare training and certificate program intended to engage entire practices in adopting sustainable, gender-affirming strategies to create healthcare environments that are culturally sensitive, culturally competent, and welcoming to TGNC.

Since gender-affirmation strategies are desperately needed during every step of the HIV treatment cascade, this program will target healthcare professionals and practice staff in both primary care settings and specialty HIV care settings.

Furthermore, in order to provide an authentic educational experience, TGNC patients will serve as content planners and speakers on this program alongside faculty who have expertise in HIV and transgender healthcare.

To learn more about this program, including opportunities to host this educational training locally, visit www.annenberg.net.

References

James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz N. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:1-17.

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html. Accessed September 15, 2017.

Sevelius J. "There's no pamphlet for the kind of sex I have": HIV-related risk factors and protective behaviors among transgender men who have sex with nontransgender men. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20:398-410.

Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al.; iPrEx study team. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:820-829.

Lall P, Lim SH, Khairuddin N, Kamarulzaman A. Review: an urgent need for research on factors impacting adherence to and retention in care among HIV-positive youth and adolescents from key populations. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(2 Suppl 1):19393.

Sevelius JM1, Patouhas E, Keatley JG, Johnson MO. Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47:5-16.

Sevelius JM, Carrico A, Johnson MO. Antiretroviral therapy adherence among transgender women living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21:256-64.

US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Office of Minority Health. The CMS equity plan for improving quality in Medicare. September 2015. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/OMH_Dwnld-CMS_EquityPlanforMedicare_090615.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2017.

Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D. Managing uncertainty: a grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:22-29.

Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. "We don't exist": a qualitative study of marginalization experienced by HIV-positive lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender women in Toronto, Canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:17392.

Gates GJ. How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2017.