Since the COVID-19 pandemic, microlearning has emerged as an educational tactic used for patients, students and other trainees but has not been commonly applied in educating practicing healthcare professionals (HCPs).1-4 Microlearning allows learners to maintain high engagement with its simple, succinct and easy-to-digest delivery of content while avoiding mental fatigue.5

The results from a Clinical Care Options (CCO) survey of 1,186 HCPs found that HCPs could commit only 30-60 minutes per week to learning new information; few could spare more than one hour. Approximately 40% preferred to spend less than 20 minutes on each learning opportunity, and more than 50% reported that lack of time was their primary barrier to participating.

Microlearning opportunities enable a busy HCP to access and digest educational material on the go — on the way to work, while exercising, eating a meal and so on. Microlearning activities can be quickly developed and delivered in the moment of need for HCPs.

We evaluated the use of virtual, on-demand microlearning activities in this focused educational program titled, “Sweet 16: Time to Complete Meningococcal Vaccines,” in partnership with the Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine (SAHM).

Microlearning Program Design and Deliverables

This program comprised of three short, engaging, CME-certified ClinicalThought commentaries with three associated podcasts. The commentaries provided concise, thought-provoking contributions from clinical experts and were sent by email to a broad network of HCPs. They were also offered as web-based education. Each commentary focused on a knowledge or performance gap that was measured with interactive questions to gauge baseline comprehension and behaviors. Questions were then asked again after completing the activity to measure changes in response. The three audio podcasts, derived from the commentaries, made the content more accessible for learners to consume on the go through their chosen podcast channel(s).

Both activity types catered to busy HCPs, offering efficient learning to optimize convenience and address the known issue of time being a limiting factor for completing continuing medical education. The content was formatted so learners could complete each activity in just 15 minutes.

Microlearning Program Goals

The program goal was to enable HCPs to overcome barriers to meningococcal vaccination such as filling knowledge gaps about vaccine recommendations, responding to patients and/or parents with vaccine refusal or hesitancy, and addressing social determinants of health. We did this by providing an overview of meningococcal disease and vaccines, along with practical tools to overcome barriers to immunization in adolescents, with a goal to reach 3,900 learners through the microlearning activities.

One pre-activity/post-activity question was created for each of the three ClinicalThought commentaries based on the program’s three learning objectives to measure competence and intended individual behaviors. Case-based questions were used. In some cases, rating questions were used to evaluate the HCPs’ intent to change their clinical practice.

Preliminary Results Summary

ClinicalThought commentaries and podcasts were released monthly, starting in late September 2022. Preliminary data are available through March 10, 2023. Data analysis is ongoing.

Table 1. Learner Actions

|

Program Traffic

|

Number of Learners

|

Deliverable

|

Activity Use

|

|

Unique Learners*

|

19,553

|

Podcast Downloads

|

990

|

|

Cumulative Learning†

|

25,092

|

Commentary Views

|

24,102

|

*Number of individuals who access a given activity; reported once per program, regardless of the number of visits.

†Sum of learners from all individual activities within a given program; individuals are only counted once per in this metric.

Table 2a. Learner Breakdown by Profession

|

Profession

(n = 13,584)

|

Learners by Profession, %

|

|

Physician

|

53

|

|

Pharmacist

|

19

|

|

Nurse Practitioner

|

10

|

|

Nurse

|

3

|

|

Other HCP

|

3

|

Table 2b. Learner Breakdown by Specialty

|

Specialty

(n = 13,549)

|

Learners by Specialty, %

|

|

Infectious Disease

|

58

|

|

Family Medicine

|

24

|

|

HIV

|

20

|

|

Internal Medicine

|

3

|

|

Psychiatry

|

1

|

Table 3. Preliminary Assessment Question Data

|

Question

|

Interim Number of Responders

|

Pretest: Optimally Correct

|

Interim Number of Responders

|

Posttest: Optimally Correct

|

Absolute Change

|

|

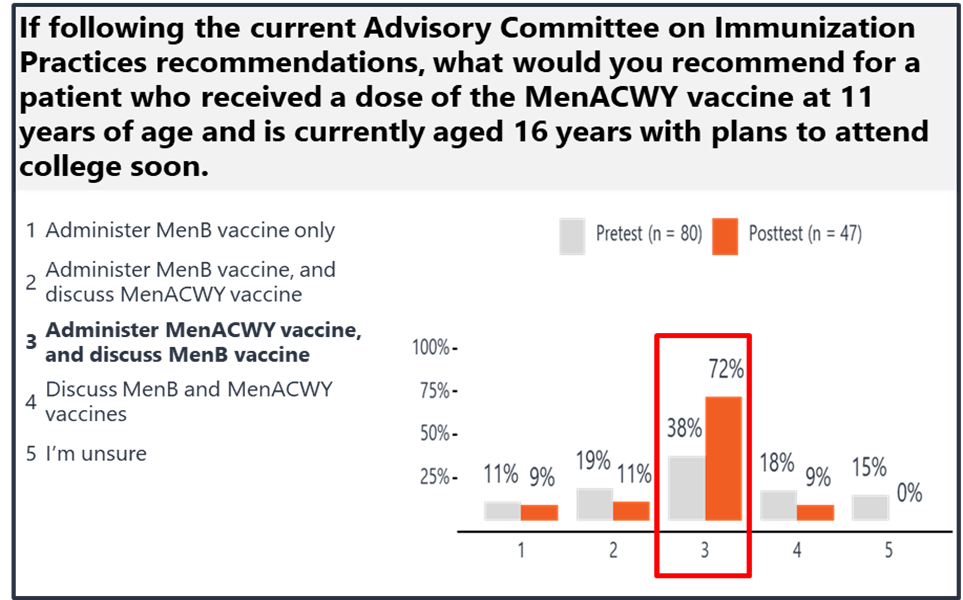

If following current ACIP recommendations, what would you recommend for a patient who received a dose of the MenACWY vaccine at 11 years of age and is currently aged 16 years with plans to attend college soon?

|

80

|

38%

|

47

|

72%

|

34%

|

|

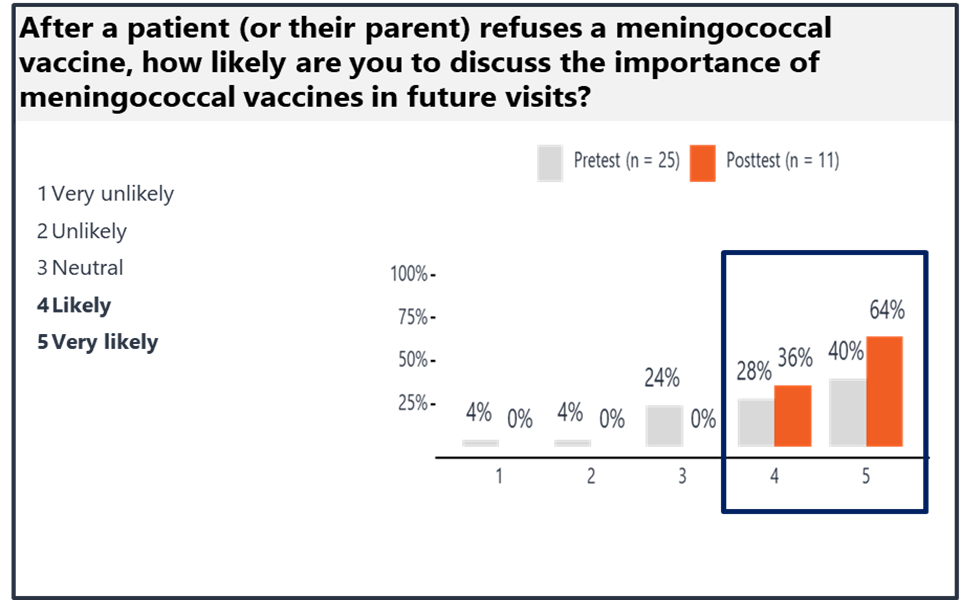

After a patient (or their parent) refuses a meningococcal vaccine, how likely are you to discuss the importance of meningococcal vaccines in future visits?*

|

25

|

68%

|

11

|

100%

|

32%

|

|

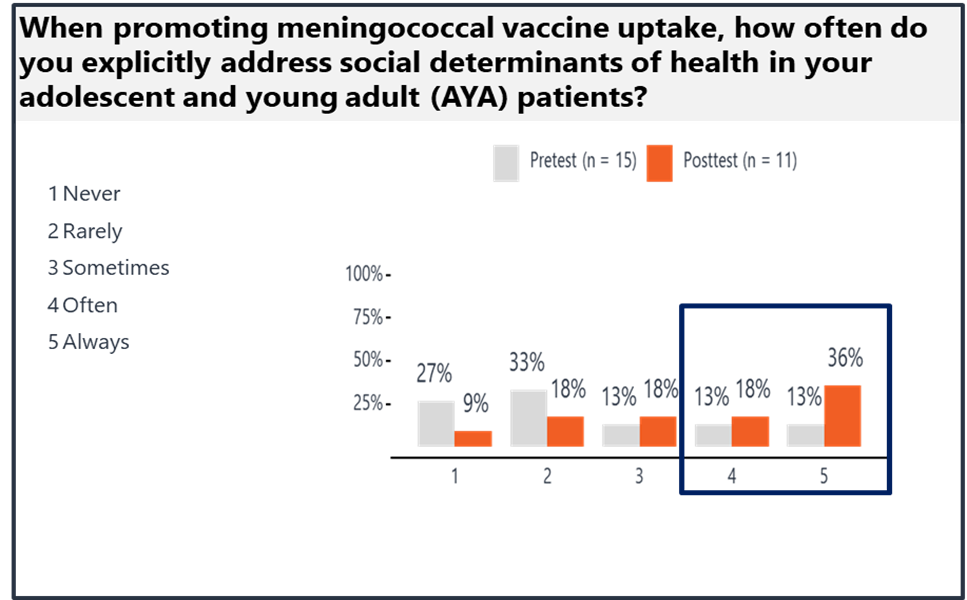

When promoting meningococcal vaccine uptake, how often do you explicitly address social determinants of health in your adolescent and young adult patients?†

|

15

|

26%

|

11

|

54%

|

28%

|

*Optimal responses were “likely” and “very likely.”

†Optimal responses were “often” and “always.”

After only a few months, we exceeded our target number of learners by more than five-fold. The three podcasts have been downloaded by nearly 1,000 learners during that same time frame.

Through use of carefully articulated assessment questions, we demonstrated an intent to change practice, with an absolute increase in correct pre-activity/post-activity test responses ranging from 28% to 34%.

When reviewing responses for each assessment question, we were able to gauge specific competence and behavioral changes. In the first assessment question, baseline knowledge gaps were observed. Teaching was clearly effective based on post-activity test responses (Figure 1). We observed only a small portion of learners still uncertain of the differences between MenACWY and MenB vaccination recommendations.

Figure 1. Breakdown of Assessment 1 Responses

For the other two assessment questions, rating scales measured potential changes in clinical practice behaviors. After completing the activity, 100% of HCPs reported that they were “likely” or “very likely” to discuss the importance of meningococcal vaccines in future patient visits despite initial refusal by the patient or parent (Figure 2). At baseline, 60% of HCPs reported “never” or “rarely” addressing social determinants of health explicitly in their adolescent and young adult patients (Figure 3). After completing the activity, more than one half of the respondents answered “often” and “always.”

Figure 2. Breakdown of Assessment Question 2 Responses

Figure 3. Breakdown of Assessment Question 3 Responses

Discussion

Several factors led to the success of this microlearning program. First is the feasibility of sharing bite-sized teaching through email, increased access to CME-accredited ClinicalThought commentaries via the learner’s inbox. This allowed learners increased flexibility, fitting learning opportunities into their busy schedule with ease. Educational material can be easily shared with CCO learners based on their profession, specialty and areas of interest, expanding our reach to the masses.

CCO’s educational platform embraces the concept of multichannel learning, with programs like this one carefully designed to offer education through different formats. Content was also released in audio format using podcasts. Podcasts have been a popular way for our learners to consume information because they can be accessed any time, any place, via any device.

CCO has a large established platform of learners who routinely use resources on our website to fulfill their educational needs. Our reach was further extended through our partnership with SAHM, as they shared our educational program in their member newsletter.

It is important to note the small number of learners responding to assessment questions in some of the deliverables relative to overall participation in the activities. This may be because of the time these educational activities were made available online prior to data analysis. Our preliminary analysis captured 2–6 months of data and likely underestimated the full impact of this educational program.

One area of improvement that we quickly identified was the smaller than expected portion of engagement from those in primary care. Most learners were infectious disease specialists. After identifying this issue during an interim analysis, our team increased efforts to reach those in primary care who care for adolescent patients for whom meningococcal immunization is recommended. Our preliminary results identified additional education needs even within the infectious disease specialty group, so education to improve competence for both specialists and generalists is warranted.

In addition, there are opportunities to leverage technology to embed interactive features such as assessment questions and discussion boards within the email without requiring additional clicks. As we investigate ways to achieve this, we have pursued other efforts to increase learner engagement. Through collaboration with our marketing team, we have increased learner participation through various marketing strategies, such as utilizing engaging “teasers” in emails and activity promotion on social media.

Conclusion

We believe our successes from this educational program may provide useful to others to consider creating programs solely comprising microlearning activities, especially when budgets and resources are limited. The simple — yet effective — format of ClinicalThought commentaries and associated podcasts allowed HCPs to receive expert-led, evidenced-based, timely education in digestible, varied formats. We found that microlearning did not sacrifice the ability to assess outcomes and improve learner knowledge and competence.

References

- Dahiya S, Bernard A. Microlearning: the future of CPD/CME. J Eur CME. 2021;10:2014048.

- Nowak G, Speed O, Vuk J. Microlearning activities improve student comprehension of difficult concepts and performance in a biochemistry course. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2023;15:69-78.

- Janssen A, Shah K, Rabbets M, et al. Feasibility of microlearning for improving the self-efficacy of cancer patients managing side effects of chemotherapy. J Cancer Educ. 2023;Epub ahead of print.

- Cai F, Santiago S, Southworth E, et al. The #ObGynInternChallenge: reach, adoption, implementation, and effectiveness of a microlearning SMS-distributed curriculum. Acad Med. 2023;98:917-921.

- Shail MS. Using micro-learning on mobile applications to increase knowledge retention and work performance: a review of literature. Cureus. 2019;11:e5307.

Jacqueline Meredith, PharmD, BCIDP, received her Doctorate in Pharmacy at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and completed her PGY1 pharmacy residency at Indiana University Health in Indianapolis, and PGY2 Infectious Diseases (ID) pharmacy specialty residency at the University of North Carolina Medical Center in Chapel Hill. Dr. Meredith is a scientific director in ID at Clinical Care Options (CCO). In her role, she is responsible for developing and managing content for medical education. Prior to joining CCO, Dr. Meredith spent seven years in clinical practice as an ID and antimicrobial stewardship (ASP) clinical pharmacist team lead. In this role, she led numerous ASP initiatives, research and quality improvement projects; authored peer-reviewed publications; educated healthcare professionals; and precepted students and residents. Dr. Meredith is pharmacy board certified in ID and actively involved in professional pharmacy organizations including the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists and American College of Clinical Pharmacy ID PRN.

Jacqueline Meredith, PharmD, BCIDP, received her Doctorate in Pharmacy at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and completed her PGY1 pharmacy residency at Indiana University Health in Indianapolis, and PGY2 Infectious Diseases (ID) pharmacy specialty residency at the University of North Carolina Medical Center in Chapel Hill. Dr. Meredith is a scientific director in ID at Clinical Care Options (CCO). In her role, she is responsible for developing and managing content for medical education. Prior to joining CCO, Dr. Meredith spent seven years in clinical practice as an ID and antimicrobial stewardship (ASP) clinical pharmacist team lead. In this role, she led numerous ASP initiatives, research and quality improvement projects; authored peer-reviewed publications; educated healthcare professionals; and precepted students and residents. Dr. Meredith is pharmacy board certified in ID and actively involved in professional pharmacy organizations including the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists and American College of Clinical Pharmacy ID PRN.

Sarah L. Anderson, PharmD, BCACP, BCPS, FASHP, FCCP, earned her BA degree in biochemistry from the University of Colorado at Boulder and her PharmD degree from the University of Colorado School of Pharmacy. Upon graduation, Dr. Anderson completed a PGY1 Pharmacy Practice residency and a PGY2 Ambulatory Care/Family Medicine residency. Dr. Anderson has 16 years combined experience in pharmacy and healthcare education, clinical practice, and scholarly activities. She has authored nearly 40 peer-reviewed publications and several book chapters. She is a prolific national speaker and the recipient of numerous local and national awards, including the Next-Generation Health-System Pharmacist award and Colorado Pharmacist of the Year award. Dr. Anderson is dually board certified in pharmacotherapy and ambulatory care and is a fellow of both ASHP and ACCP. She is highly active in ACCP, ASHP and the Colorado Pharmacists Society. Dr. Anderson currently serves as a scientific director in infectious diseases at Clinical Care Options. In her role, Dr. Anderson is responsible for the development of live and online medical education programs, including national and international faculty management; content creation, editing and preparation for online and print production; assisting in development of marketing materials; and analysis and publication of educational data. Her professional goal is to create and deliver scientifically and educationally sound continuing medical education to healthcare professionals around the world.

Sarah L. Anderson, PharmD, BCACP, BCPS, FASHP, FCCP, earned her BA degree in biochemistry from the University of Colorado at Boulder and her PharmD degree from the University of Colorado School of Pharmacy. Upon graduation, Dr. Anderson completed a PGY1 Pharmacy Practice residency and a PGY2 Ambulatory Care/Family Medicine residency. Dr. Anderson has 16 years combined experience in pharmacy and healthcare education, clinical practice, and scholarly activities. She has authored nearly 40 peer-reviewed publications and several book chapters. She is a prolific national speaker and the recipient of numerous local and national awards, including the Next-Generation Health-System Pharmacist award and Colorado Pharmacist of the Year award. Dr. Anderson is dually board certified in pharmacotherapy and ambulatory care and is a fellow of both ASHP and ACCP. She is highly active in ACCP, ASHP and the Colorado Pharmacists Society. Dr. Anderson currently serves as a scientific director in infectious diseases at Clinical Care Options. In her role, Dr. Anderson is responsible for the development of live and online medical education programs, including national and international faculty management; content creation, editing and preparation for online and print production; assisting in development of marketing materials; and analysis and publication of educational data. Her professional goal is to create and deliver scientifically and educationally sound continuing medical education to healthcare professionals around the world.