As we all know, continuing medical education is designed to improve clinician knowledge and competence, improving clinician performance and closing gaps in practice. Although numerous methods are utilized to measure the impact of our educational efforts, the most common among our profession is assessing change through pre- and post-testing. When this method of assessment is used, we trust it to indicate how successful an educational program has been by documenting the changes that have occurred. We also rely on assessments to provide data that inform current activity refinements and define future educational needs, all designed with our original goal in mind: to close practice gaps and ultimately enhance patient care.

The Problem of Partial Knowledge

Performance on a test, however, rarely fully and accurately demonstrates the impact of the educational intervention. In almost any traditional assessment, there is a large and often significant confounding influence conferred by speculation, with learner confidence significantly impacting their ability to retain and apply what they have learned. Our common use of multiple-choice questions provides a hidden loophole in the form of guessing and does not recognize the impact of learners who have doubt.1, 2 Simply put, a correct answer that was randomly chosen is not an indicator of true knowledge.

CBA Digs Deeper

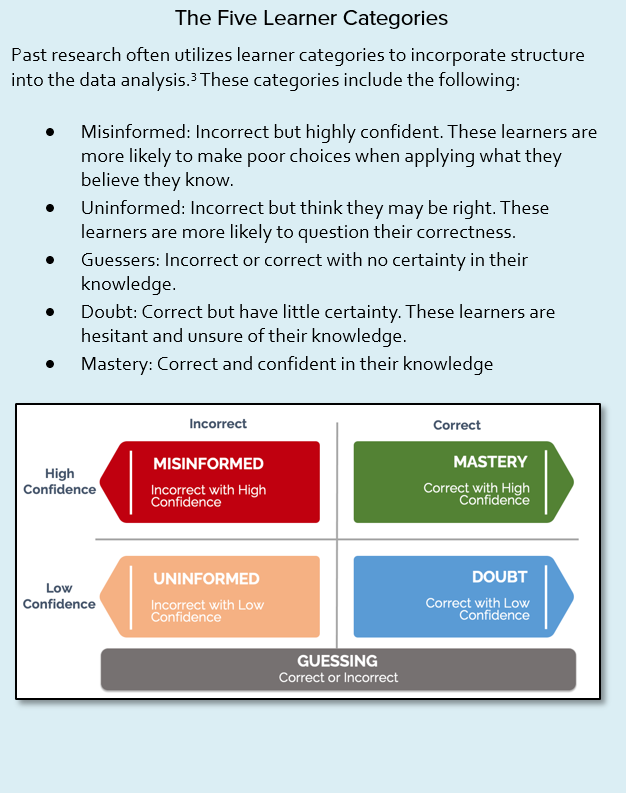

Confidence-based assessment (CBA) applies a two-step methodology to standard MCQs acknowledging the spectrum of learner responses, providing a bridge from traditional assessment to a more complete picture of a learner’s understanding and belief. When CBA is incorporated into assessments, the results will identify those learners who are guessing as well as the ones who have doubt in their understanding or have high confidence in their knowledge, creating additional understanding of answers beyond simply correct or incorrect. In this way, CBA shines a spotlight on true educational impact.4

Educators have been employing various tactics to measure learner confidence for decades: published research can be traced back into the 1930s when educators were attempting to create a scoring method that incorporates learner correctness with learner confidence. Since that time, there have been dozens of research papers published on the topic and CBA is currently used by hundreds of graduate and post-graduate programs. Multiple studies have found that a test that incorporates CBA not only measures a learner’s correctness, but also provides them with a structured opportunity to reflect on their attitudes around that knowledge or competence. The small pause required to respond to a CBA confidence query increases learner engagement, encourages reflection and strengthens the ability to self-assess, all important facets of truly effective medical education.3 CBA also provides an opportunity to drive remedial education. According to Curtis, “This combination of being incorrect and unsure is considered to provide a very appropriate ‘teaching moment,’ in which the student is especially responsive to faculty feedback and to learning ... In this way, an examination can result in learning during an assessment, which is an example of test-enhanced learning.” In a 2003 study by Hunt, learners who indicated high confidence in their knowledge retained 91% of their learned knowledge while those with doubt retained only 25% after one week. Other studies have indicated that even when students/learners pass an exam, a lack of confidence will severely impact their ability to apply what they have learned.

"Learners who indicated high confidence in their knowledge retained 91% of their learned knowledge while those with doubt retained only 25% after one week."

Applying CBA

Applying CBA

Measuring confidence in CME is not a new concept but is often done by asking learners to rate their overall confidence in a particular topic before and after the educational intervention. This methodology focuses on the learner’s overall confidence and lacks the ability to tightly couple to a learner’s belief in their specific knowledge and competence, nor does it effectively create the teachable moments described above. The strength of tightly coupled CBA (confidence and correctness) is related to measuring how completely a learner embraces their understanding of each question.4 To uncover and measure guessing and doubt, CBA gauges a learner’s confidence in their chosen answer on each question. This is done by layering an additional confidence query using some version of the straightforward phrases “I’m sure,” “I think” and “I’m guessing.” This method encourages learners to slow down to reflect on their answer and their own body of knowledge. The additional data collected for each question increases the overall analysis beyond two points of data, right or wrong, and allows the assessment of a more granular approach with multiple points of data, effectively allowing the education provider to peer into the cognitive state of a learner. Now the educator can analyze correctness coupled to the learner’s confidence (guessing, low or highly confident), leading to stronger statistical and predictive reliability of assessment data.3

CBA Advances Medical Education

Understanding the nuances of clinician learning is crucial to the success of education and has an impact on the future performance of learners. The advantages of CBA are particularly valuable in the decision-rich field of medical education, where misplaced confidence can lead to serious consequences.3

Research indicates that clinician learners’ realism about their level of knowledge has an effect on their behavior as practitioners. Overconfident practitioners — the “misinformed” learners identified by CBA — present a real risk to patients. These are the ones who may refuse outside opinion and bypass lab tests, possibly delivering an incorrect diagnosis and/or inappropriate treatment plan, with additional risk of complications. Under-confident practitioners — “uninformed” or “in-doubt” learners — may routinely order excessive medical tests in order to be certain of a diagnosis, potentially wasting their patients’ time as well as healthcare resources.5

Testing that incorporates CBA provides a robust analysis of healthcare practitioner learning and confidence in what they know, allowing the education provider to direct special attention to learners who are guessing, who lack confidence in their knowledge (the uninformed or in doubt) or have high confidence but are incorrect (the misinformed). This depth of data will identify important unmet learning needs, providing valuable opportunities to improve future assessments that will raise the bar on medical education, future healthcare practitioner performance and, ultimately, patient outcomes.

References

- Curtis DA, Lind SL, Boscardin CK, Dellilnges M. Does student confidence on multiple-choice question assessments provide useful information? Med Education. 2013;47:578-584.

- Novacek P. (2013). Confidence-based assessments within an adult learning environment. IADIS International Conference on Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age, CELDA 2013. 403-406.

- Gardner-Medwin AR, Gahan M. Formative and summative confidence-based assessment. Proceedings of the 7th International Computer-Aided Assessment Conference [Internet]; July 2003; Loughborough, United Kingdom. Available from: https://tmedwin.net/~ucgbarg/tea/caa03a.pdf.

- Ghadermarzi M, Yazdani S, Pooladi A, Bahram-Rezaei M, Hosseini F. A comparative study between the conventional MCQ scores and MCQ with the CBA scores at the Standardized Clinical Knowledge Exam for Clinical Medical Students. J Medical Education. 2015;14:6-12.

- Hausman CL, Weiss JC, Lawrence JS, Zeleznik C. Confidence weighted answer technique in a group of pediatric residents. Medical Teacher. 1990;12(2):163-168.